Summary

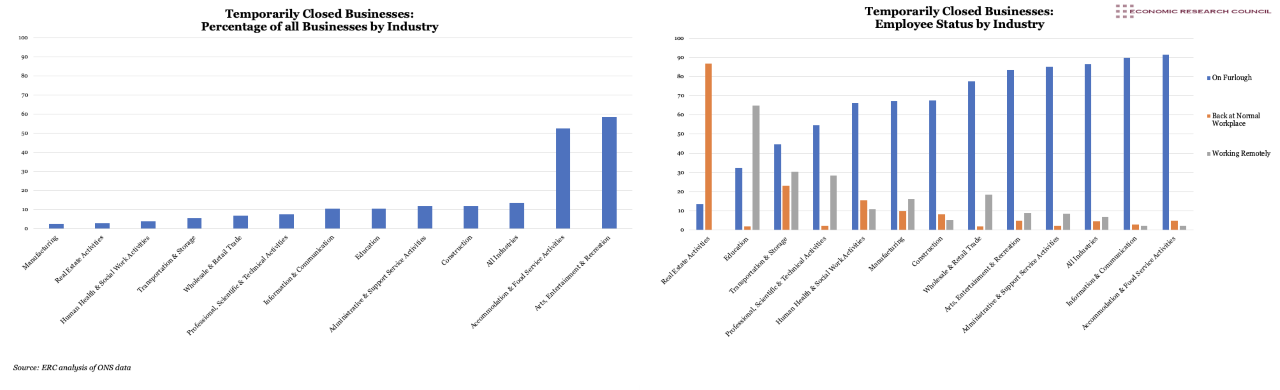

According to the latest Business Impact of Covid-19 Survey conducted by the Office for National Statistics, 13.5% of all UK businesses have temporarily closed or paused trading, during the lockdown, with 86.4% of workers in these businesses on furlough. However, underlying these aggregate figures are significant variations by industry sector. The hospitality and entertainment sectors have borne the brunt of the economic shock, in contrast to most other industries which have seen a much lower proportion of temporary closures. Moreover, in some sectors, such as education, a large proportion of employees have continued to work, despite their establishments being temporarily closed – providing evidence of a more positive outlook for these industries.

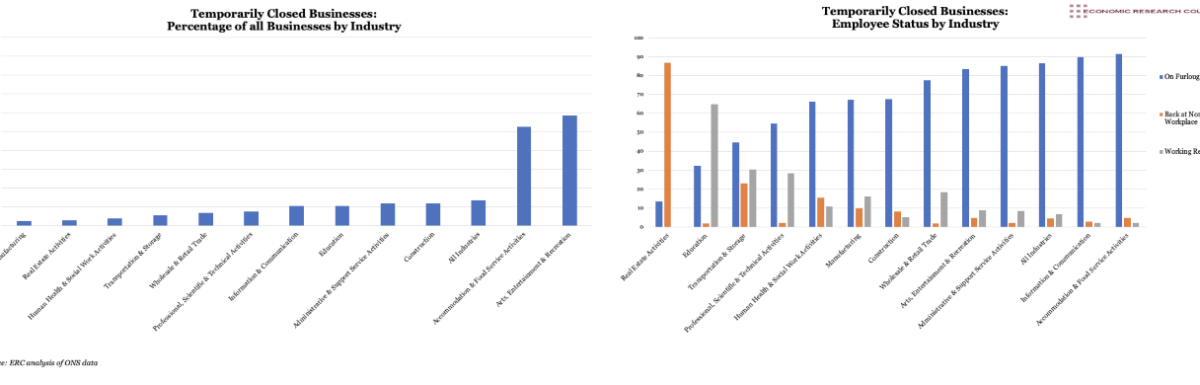

These charts provide an interesting insight into how the economic impact of Covid-19 differs by industry. The two sectors have been hardest hit by the crisis – hospitality (Accommodation and Food Services Activities) and entertainment (Arts, Entertainment and Recreation) – in which 53% and 59% of businesses respectively have been forced to temporarily close. Moreover, 91% of hospitality workers, and 84% of entertainment workers, in these temporarily closed businesses were on furlough during the lockdown- a further indicator of the significantly reduced activity in these industries.

However, all other industries have experienced a lower closure rate than the 13.5% average. Surprisingly, the manufacturing sector emerges as the most resilient sector in the data, in which only 2.6% of firms have paused trading during the lockdown period.

Significantly, in several other sectors there also is evidence of relatively high levels of ongoing activity in those businesses that were temporarily closed. For example, although 10% of establishments in the education sector were temporarily closed, 65% of the employees continued to work remotely during the period – presumably as they adapted to deliver their services online or created teaching resources for use in the new academic year. In addition, in the transportation and real estate sectors, 54% and 87% respectively of the employees of temporarily closed firms continued to work. This is in contrast to the information and communication industry, where 10% of firms closed temporarily, and only 5% of those firms’ employees continued work during the lockdown.

What do the charts show?

The first chart displays the percentage of UK businesses that have temporarily closed in each industry sector. The second chart shows the status of the workforce in those businesses that have temporarily closed, again in each industry sector. The blue bars display the proportion of the workforce on furlough, the orange bars show the proportion back at their normal workplace, and the grey bars display the proportion working remotely. The data originates from the latest fortnightly business survey conducted by the Office for National Statistics, covering the period from 1st June to 14th June 2020. One further release of more recent data has been issued by the ONS, however as a reduced number of businesses responded, we have chosen to display the more complete older data.

Why are the charts interesting?

These charts may provide some insight into the likely pace of the recovery in certain sectors, as lockdown restrictions are eased allowing consumer and business confidence to return gradually. The combination of the high closure rate and high proportion of workers on furlough highlights the particular challenges of the hospitality sector. Estimates of the time it will take for the industry to recover vary significantly. Optimists such as commercial real estate firm, Knight Frank, estimate 18 months, whereas Professor Alasdair Smith of the Scottish Fiscal Commission quoted in the Evening Express stated that the industry may never recover fully. The industry employs 3 million people and, when the government’s Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme ends, a large number of furloughed may face redundancy. Recent government initiatives aimed at supporting the sector, such as the temporary cut in VAT and ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme, may not significantly change this. The hospitality union has proposed a scheme called the ‘National Time Out’ which aims to save 2 million jobs by requiring landlords to introduce a nine-month rent holiday. However, this would have a significant economic cost for the property industry and likely be met with vociferous opposition from landlords.

Conversely, the education sector appears to be responding effectively to the new challenges by adapting to combine the online and physical delivery of its services. Adam Nordin of Goldman Sachs has noted how the crisis could ‘dramatically accelerate the long-term acceptance of online learning’ and that, as a result of the pandemic, higher education institutions are likely to adopt ‘enterprise-level technologies, in the same way we saw the healthcare industry adopt software and data analytics.’. A survey by UK Universities International suggests that most universities are quickly moving in this direction, with 82% now considering how Covid-19 will impact their long-term strategy for international students. Some 92% of these universities are expecting a lasting increase in the provision of online classes.

However, in other sectors, the proportion of businesses forced to close temporarily has been much lower. Moreover, many firms which have done so have nevertheless continued to operate in the background, such as in the education sector, while also taking advantage of the cost savings available under the government’s Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme – suggesting they are better positioned for the recovery.

It should be noted that the hospitality sector employs a much larger proportion of lower paid workers than a sector such as education, which has a higher number of more skilled workers able to work remotely – increasing the security of their employment during and after the lockdown. In other words, the worse affected sectors by the lockdown have tended to be the ones with the lower paid, and more precarious jobs, as this often correlates to the need for physical presence. This disproportionate impact on lower income groups is likely to have a lasting effect. A recent study from VoxEU concluded that pandemics increase a country’s GINI coefficient (a marker of income inequality) by approximately 1.25% five years after the start of a pandemic- all of which will undoubtedly shape government welfare benefits policy in the coming years.