Summary

Now a fully-fledged economic, as well as health, crisis; the Coronavirus outbreak’s potential to trigger a global economic recession is clearly a chief worry for finance leaders across the world. Quarantine measures, social distancing and mandatory closures of public spaces are set to depress consumer confidence. CFOs are concerned not just about plummeting consumer demand, but also their ability to maintain workforce productivity and smooth supply chains in these unprecedented times. All but the most robust of companies are facing increased risk of failure, and the commensurate rise in unemployment will further feed into a rather negative economic outlook. With 48% of surveyed CFOs citing a fear of financial impact on future periods, it is clear that uncertainty about the duration of the crisis is further hampering business’ ability to plan and forecast. In a similar survey of 4000 individuals by Deloitte on 12th March, most respondents felt that economic activity would pick up by the second half of the year. The UK government have forecast that at any given point, through either personal sickness or a need to care for relatives, some 20% of the workforce may be absent. Given how fast developing the situation remains, and how the varied responses from each nation state have been in both extent and pace, the recovery may not form a consistent picture globally.

What does the chart show?

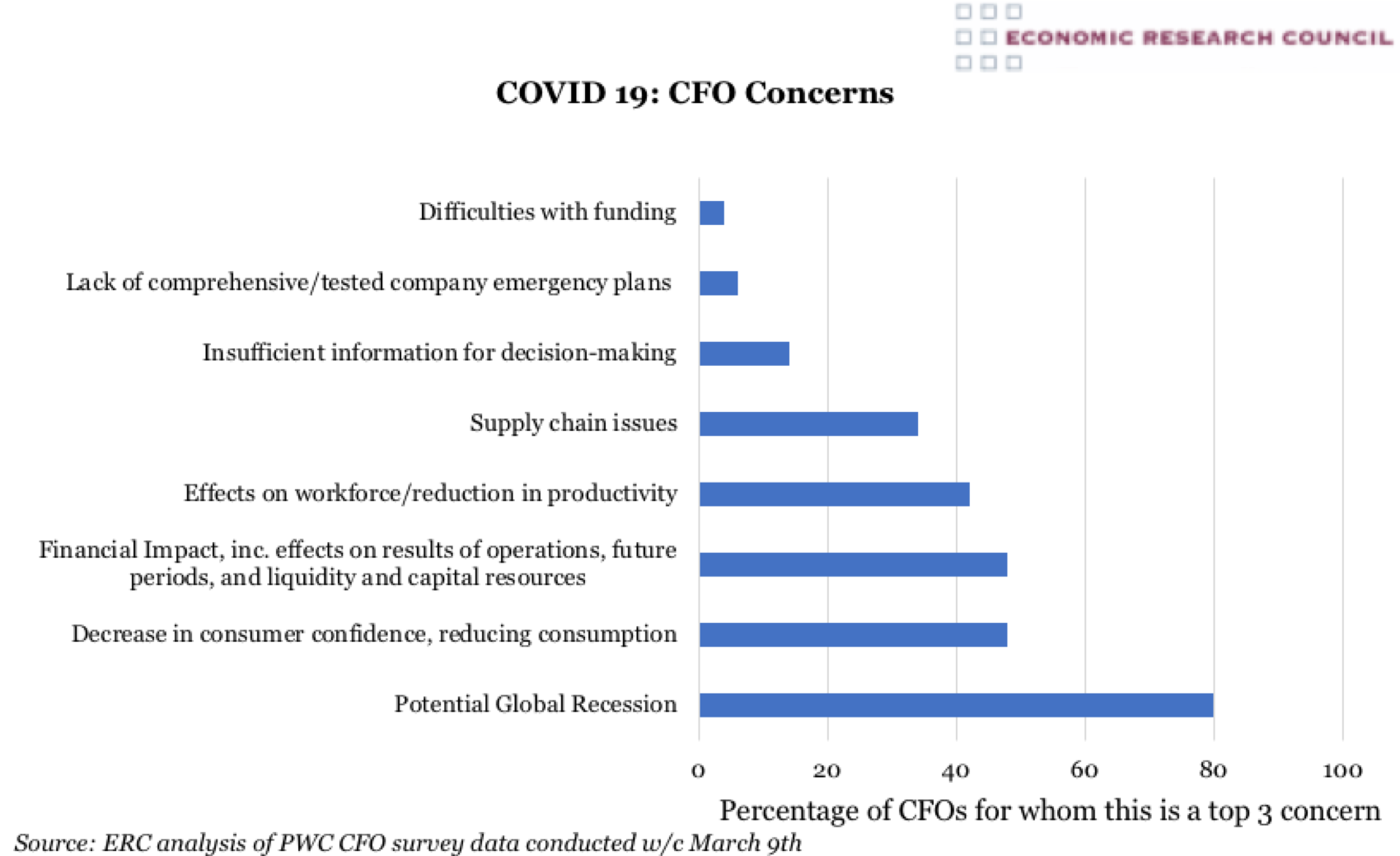

The chart displays the result of the latest survey of Chief Financial Officer sentiment from PWC. The respondents are 50 CFOs drawn from Fortune 500 companies and they were surveyed on March 11th. The question was ‘What are your top 3 concerns re COVID 19?’.

Why is the chart interesting?

Markets have been in a state of panic, in part due to Trump’s unexpected suspension of air travel from Europe to the US as well as the ECB’s hint that it would be disinclined to prop up Italian debt markets in response to the crisis. Last week’s market turmoil appears to be calming somewhat in anticipation of further government measures to assist households and business. The response in the UK has been received with mixed levels of enthusiasm. The Bank of England used what little leeway remains to further loosen monetary policy just prior to Rishi Sunak’s budget. The budget, which was uncharacteristically fiscally generous, has nonetheless still been criticised for not going far enough to protect renters vs home-owners or ensure Statutory Sick Pay at levels that are sustainable for individuals (particularly those with dependents). As the big picture emerges, no doubt there will be further aggressive measures from the Treasury to mitigate the impact of the pandemic.

Central Banks are likely to continue with asset purchases and more QE to increase liquidity. ‘Emergency’ measures that first began following the 2008 crisis are now a new normal and any sign of their ending is now gone.

German authorities have offered unlimited loans to businesses, a move that will likely be emulated elsewhere. However given the productivity problem in the UK, some worry that such a move will prolong the life of unviable businesses and cause future problems.

Instruments to deliver economic relief will vary by nation, but will most likely utilise existing tax and benefits operations, whether via suspension of means testing for benefits, income tax reductions and closer linking statutory sick pay to individuals’ salaries (such as in France and Portugal, where the government is sharing the cost with employers). Benefits in kind, such as free school meals following school closures will require alternative strategies, none of which have been offered to date.

Nations which are undertaking more direct policies include Singapore, where the government is paying private sector salaries for three months, and Hong Kong, where every adult has received $1000. The appetite for the government to offer significant corporate support has increased too- with airlines appearing at the front of the queue, similar to post 9/11.

This economic crisis, as well as the virus, is truly novel- it is not caused by bursting financial bubbles, deficient demand or underutilised potential. Revenues that would normally come from the population producing, earning and spending is evaporating. This goes some way to explaining the shift in the economic narrative- it is increasingly accepted and advocated that it is only governments who now can, and need to, borrow to both invest and offer injections of cash to households and businesses.