Summary

As UK’s bank rate hits a 13-year high, its impact reverberates through the economy, with disposable incomes shrinking and inflation spiralling. Amidst this, debates rage on the true culprits behind soaring inflation. We present an incisive analysis of the UK’s economic landscape, from the plight of mortgagors and renters to the potential pitfalls of traditional monetary policy.

What does the chart show?

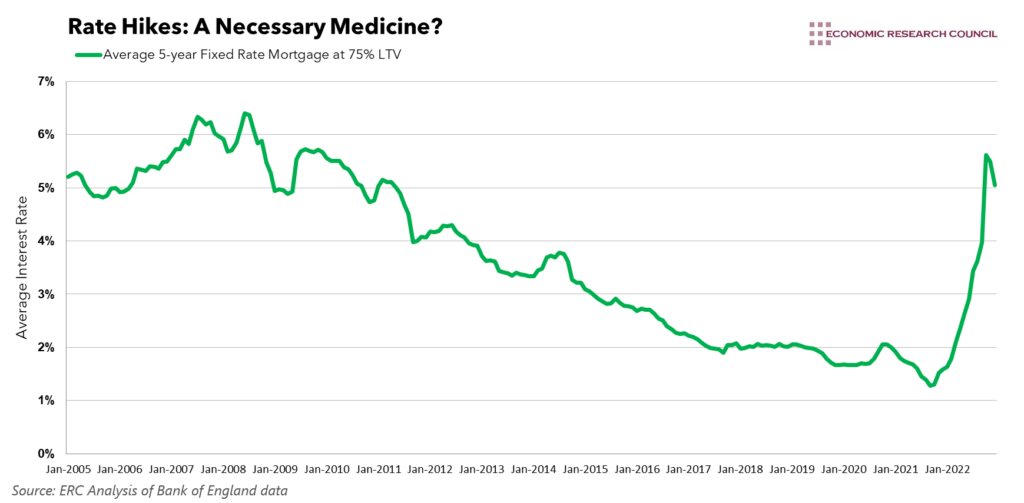

The chart shows the average quoted mortgage rates for 5-year fixed-rate mortgages at a 75% loan-to-value ratio, from 2005 to the end of 2022.

Why is the chart interesting?

On June 22nd, the UK’s bank rate witnessed its 13th consecutive increase, shifting from 4.5% to 5%. This marks the highest level since 2008, a deliberate move to control inflation and steer the economy toward the traditional 2% mark, while simultaneously aiming to prevent a recession. Although UK inflation, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, is predominantly a supply-side issue, primarily triggered by ‘spectacular increases in energy prices’. While the £70bn furlough scheme, a pandemic-era fiscal stimulus, has undeniably had some influence on today’s prices, it pales in comparison to the effects of the ongoing conflict in Europe. The disruption of global supply chains and the introduction of economic sanctions have culminated in the rising price of fossil fuels, which has fed through to the price level in general. Today’s announcement of 7.3% CPI inflation, raises the question; how much of this figure comes from within the UK economy, and is monetary policy the appropriate way to correct it?

Successive increases in interest rates are significantly depleting the disposable incomes of individuals who, enticed by the 2021 post-pandemic stamp duty holiday and prevailing low-interest-rate environment, have opted for mortgages. If current inflation were a consequence of too much money chasing after too few goods, this hit to disposable incomes could have been a desirable effect – though, with disposable incomes already slashed by the cost of living crisis and a decade of wage stagnation, the most recent hike in the bank rate largely serves to worsen material conditions for many. The conclusion of fixed-rate mortgages is a significant factor to the 60% of mortgaged UK households – representing 19% of UK adults – projected to allocate over one-fifth of their incomes solely to their mortgage. This is up from 36% of mortgagors in the same position in only March 2022. As landlords raise rent to keep up repayments on buy-to-let mortgages, the income-squeezing effects of greater interest rates are felt by even non-indebted renters.

There’s a salient aspect to monetary policy decision-making that is critical to understanding its efficacy, and it’s glaringly absent in the current discourse: the time lag. Economists commonly recognise an approximately 18-month delay between the implementation of interest rate changes and their tangible impact on the economy. This is no insignificant footnote; it fundamentally alters the context in which policy decisions are made and evaluated. Policymakers must anticipate future economic conditions and adjust rates based on these predictions, essentially aiming at a moving target, a task growing increasingly difficult amidst the current economic uncertainty. The persistent focus on immediate circumstances rather than forward-looking estimations may lead to what economists refer to as ‘policy overshoot,’ where by the time the effects of a rate adjustment are felt, they’re no longer appropriate for the prevailing economic conditions. This can result in a policy-induced exacerbation of economic cycles rather than their intended moderation. In this light, it is worth querying whether the successive hikes in the bank rate, seemingly reactionary to current inflation figures, have sufficiently considered the future landscape of the UK economy and its likely position 18 months down the line.

Some analysts propose an alternative explanation for the current level of inflation, a concept known as ‘greedflation.’ This theory posits that corporate greed results in artificially inflated CPI figures. This, in turn, triggers a rise in bank rates, notwithstanding scant evidence of excessive consumption—a notion substantiated by the ONS, which reports 63% of Britons curtailing spending on non-essentials due to the mounting cost of living. Greedflation theorises that CPI figures have been artificially elevated above what would be expected given current market conditions; a result of firms gouging prices above what their production costs justify – taking advantage of inflation existing elsewhere in the economy to unsuspectingly increase prices and profit. There is potentially some data supporting this claim. In Q1, 2023, the total operating surplus of corporations in the UK exceeded a record £150bn, an increase of 26% from Q1, 2022, a year prior. At the same time, year-on-year inflation in January 2023 exceeded 10%, seemingly supporting the argument for greedflation.

However, this concept also faces substantial criticism. Critics argue that it is improbable for firms to single-handedly inflate prices purely out of greed, to such an extent that it precipitates a spike in the bank rate – Indeed, our dependence on fossil fuels exerts a far more substantial influence on prices, thus driving the call for increased bank rates. Natural gas, in particular, is so entrenched in our lives and economy, that the ongoing European conflict’s upward pressure on fossil fuel prices is undoubtedly enough to drag up prices elsewhere in the economy. Along with 85% of UK households’ reliance on gas boilers in the home, natural gas is the UK’s number-one source of electricity in general, fulfilling 40% of the national energy demand, and cementing natural gas as an essential component of British industry, including its pivotal role in plastic manufacturing. As such, the price of fossil fuels will continue to feed through to prices more generally, whether or not interest rates are hiked further, unless the UK can establish energy self-sufficiency through renewable and recyclable alternatives – rather than punishing mortgagors, renters, and consumers more generally.

The central bank does have alternative monetary policy tools at its disposal to manage inflation. The pandemic prompted the Bank of England to create £450bn through quantitative easing (QE) – the purchase of bonds and other financial instruments – to provide the economy with a cash injection, a move first seen in the UK during the recovery from the financial crisis of 2008. Inversely, quantitative tightening (QT) involves the central bank’s sale of these financial instruments, reducing the money supply, thus stifling demand; this is not a fitting solution though since, as established, much of the inflationary pressure troubling the UK at the moment is supply-side. The same challenge faces the implementation of a contractionary fiscal policy, which targets demand and consumers’ spending ability, rather than addressing supply issues. Furthermore, as 2022 experienced the most workdays lost to industrial action since the 1989 ambulance workers’ strike, and with planned strike action ongoing from teachers, rail workers and junior nurses among other occupations, a cut to disposable incomes in the form of a greater tax burden is only likely to worsen disputes over pay.

By Tyler Boruta