Summary

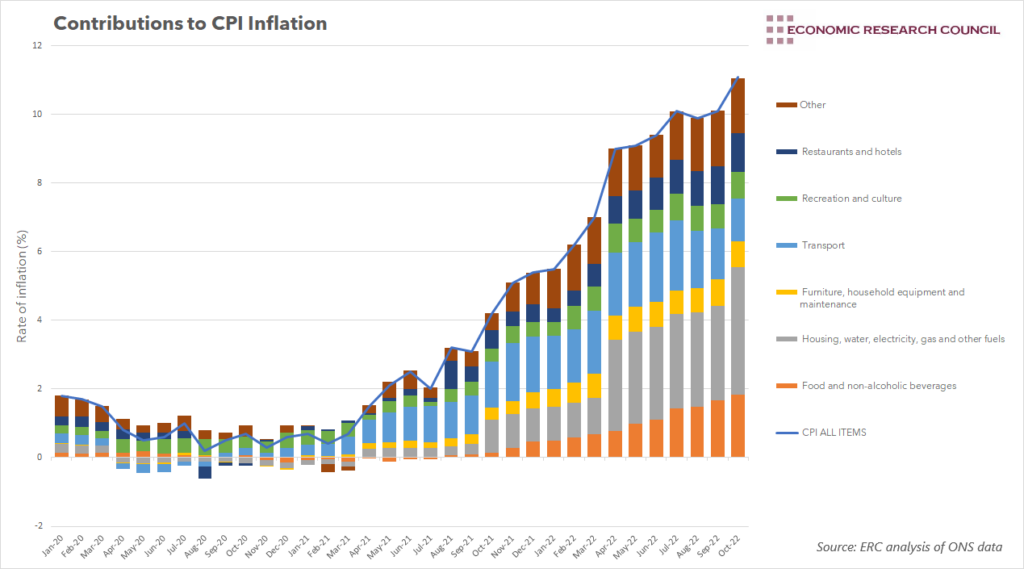

October’s headline inflation rate of 11.1% was largely led by two groups: Housing, water, electricity, gas and other fuels, and Food. This week’s chart assesses the drivers behind these groups, to judge their likely trajectory into 2023.

What does the chart show?

The chart shows the contribution to the overall year-on-year rate of inflation made by a selection of goods and services. The categories highlighted represent the top contributors to the rate of inflation in October 2022. Values above zero signify price increases compared to the same month a year earlier, whilst values below zero denote price reductions. The blue line tracks the overall year-on-year rate of CPI inflation each month.

Why is the chart interesting?

High inflation has been with us for some time now, and various narratives exist on the extent to which it will remain. Base effects have been summoned to explain a likely slowdown in inflation in 2023, as have the successive increases in the Bank rate experienced since December 2021. This week’s chart assesses the key drivers of inflationary pressure to highlight a likely trajectory through 2023.

By far the largest contributor to October’s 11.1% inflation rate was price increases within the ‘Housing, water, electricity, gas and other fuels’ category, causing a 3.7% increase in overall prices on its own. Crucially here, we see the impact of the increase in the energy price cap that took effect this month. The chart shows the successive impact that the energy price cap has had on inflation in each April and October since 2021. In these months, the impact of the Housing, water, electricity, and gas category on inflation has increased drastically compared to the month prior. In April 2021, the category jumped from a fall of 0.12% to an increase of 0.26%. In October 2021, it rose from 0.29% to 0.95%. April 2022 saw it more than double from 1.08% to 2.67%, whilst October 2022 saw an increase from 2.77% to 3.7%.

The impact of the increase in the energy price cap has not translated fully to inflation. In the mini-budget statement earlier this year, the government announced an Energy Price Guarantee, which limited the average annual bill for a typical household to around £2,500, down from what would have been £3,549. Even with this guarantee, energy prices rose by 24.3% between September and October 2022. Without it, the rise would have been almost 75% and would have led to an inflation rate of 13.8% in October.

Rather than changing twice a year, the energy price cap now updates every quarter. On 24th November, it was announced that the price cap would increase to £4,279 in January 2023. As the Energy Price Guarantee will still be in place then, this increase in the cap will not feed through to consumers, and hence have no further impact on inflation in January. The government have announced that the Energy Price Guarantee will increase to £3,000 for the average household from April 2023. While this is below the £3,702 figure predicted by Cornwall Insights, it is still well above the £1,971 figure of April 2022, meaning energy prices will still contribute significantly to inflation next year.

As the chart displays, food prices have also contributed an increasing amount to the rate of inflation, rising from 0.15% in October 2021, to 1.84% last month. These prices have risen across the various food groups. Supply chain issues were largely at fault in the latter half of last year. As these issues have begun to be remedied, rising energy costs have taken their place. Although not explicitly stated, the war in Ukraine was a key factor in the energy price discussion above, and it raises its head here again. Around 30% of the world’s wheat comes from Ukraine and Russia, so, understandably, flour, bread, and pasta have risen in price by 28%, 14%, and 34% in the last year respectively. Products that rely on wheat for feed have also seen large increases in price; 20% in the case of poultry. Overall, food prices have increased by 16.2% in the year to October, and the Institute of Grocery Distribution anticipate it rising still. They suggest a peak somewhere between 17% and 19% in early 2023, before slowing down through the rest of the year. This enormous increase in prices is cited to be caused largely by tight labour markets, continued supply chain disruptions, as well as the war in Ukraine.

Food and housing associated costs accounted for around half of the 11.1% year-on-year inflation rate experienced in October. If inflation is to fall through the next year, these categories will certainly need to do some heavy lifting. In the case of housing water, electricity, gas and other fuels, the energy price cap is the key determinant. In January 2023, when the Energy Price Guarantee will be £2,500, this price will still be 96% higher than the previous January, meaning the upwards pressure on prices remain. In April 2023 when the Energy Price Guarantee rises to £3,000, average energy prices will be 52% higher than the same time the previous year. It is not until October 2023 that the year-on-year increase in average energy prices falls to 20%, a value similar to that seen in October 2021. What these figures show is that energy prices are still likely to significantly impact inflation, but at a decreasing rate over the year. The effect it had on October’s rate of inflation is likely to continue until April when it should fall, and allow inflation to ease with it.

Food, on the other hand, is far more difficult to predict. The New York Federal Reserve’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index has been falling since the start of this year, largely led by improvements in the global shipping network. On the other hand rolling lockdowns in China threaten “shortages on shelves in Europe” according to Joerg Wuttke, president of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China. With the war still raging in Ukraine, a return to food price stability seems unlikely.

By David Dike