Summary

This chart attempts to shed light on some of the collateral impacts of the global Covid 19 pandemic, displaying one of the psycho-social effects of the pandemic that has potential to affect both the economic recovery and the state of health systems.

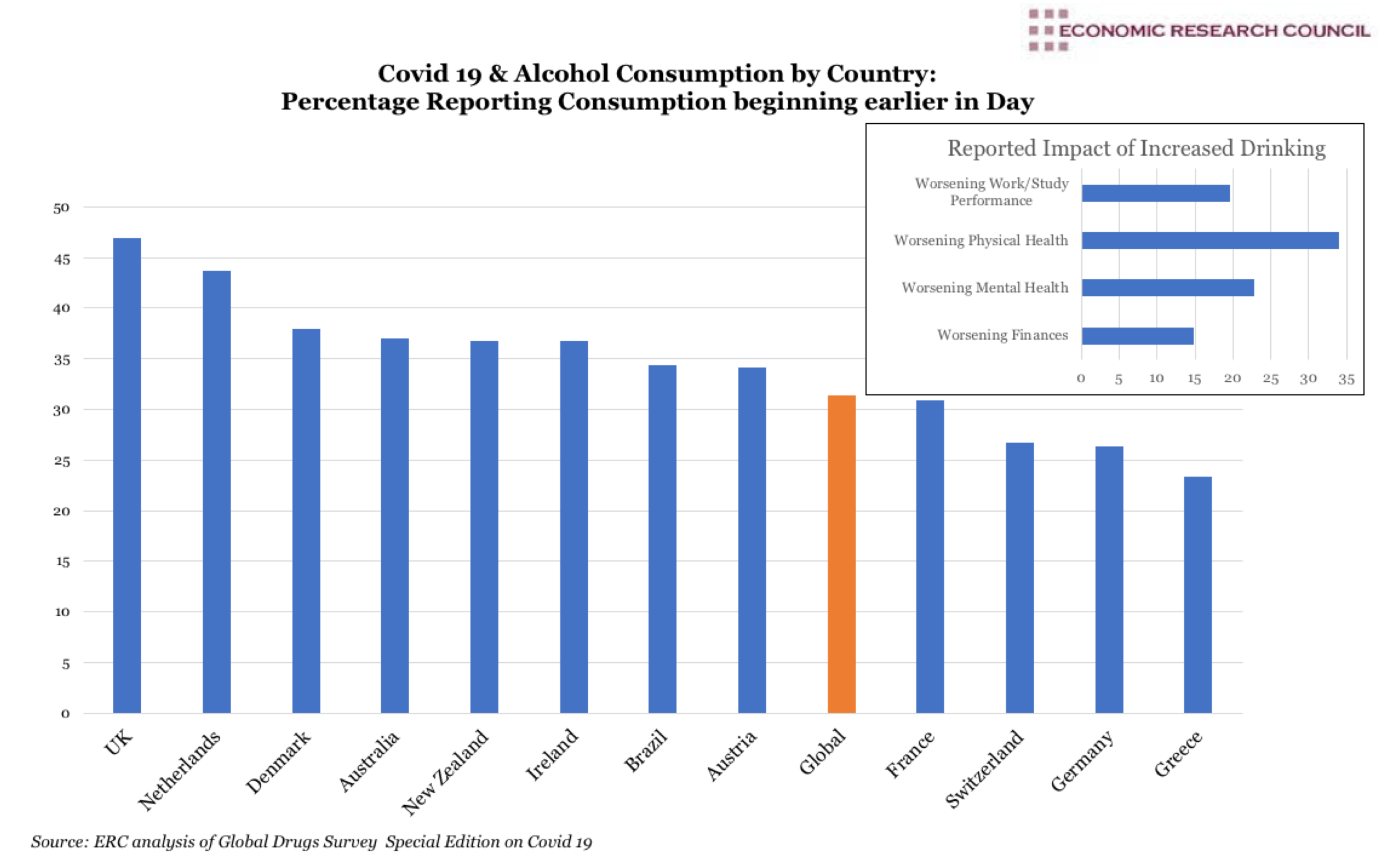

Out of the countries surveyed, the UK appears to be polling poorly in terms of many of the metrics in the wide-ranging survey. When people were asked if they were coping well with the pandemic, the UK was third from the bottom: only Brazilian and Dutch respondents reported faring worse. The survey showed that increased alcohol consumption during the pandemic is significant. 44% of respondents globally said that their drinking had increased either a little or a lot since the start of the pandemic and 31.8% said they had drunk alcohol on more than half of the last 30 days. Some 46.9% of UK respondents reported that they had started drinking earlier in the day, situating the UK approximately 50% higher than the global average of 31.4%. Only France, Switzerland, Germany and Greece are below this average. Respondents cited multiple negative impacts from their alcohol consumption, including over an eighth claiming worsening finances, over a fifth recognising deteriorating mental health, one third citing adverse physical health and nearly one fifth acknowledging a negative impact on their study and work performance. With low productivity in the UK predating the Covid 19 crisis, both increasing alcohol consumption and attendant poor mental health have the potential not just to further overwhelm the NHS, but to hamper economic recovery too.

What does the chart show?

The chart shows data from the Global Drugs Survey, the largest international, anonymous survey of personal drug and alcohol use. The above data is from their Special Edition on Covid 19, asking respondents to compare their consumption to pre-pandemic times and is based on over 40 thousand responses. The large chart displays the percentage of respondents who stated that their alcohol consumption was beginning earlier in the day than previously. The inset chart shows some aspects of respondents’ lives that have adversely impacted by their increased alcohol consumption in pandemic times, displayed as a percentage. The 12 countries displayed reached a statistically significant number of respondents, and they are displayed alongside the global average.

Why is it interesting?

The US Centre for Disease Control stated that the cost of ‘problem drinking’ to the economy in 2010 was $0.25 trillion, although they highlighted the likely cost was far higher. Although this figure included healthcare, law enforcement and accident costs, 72% of the figure stemmed from reduced job performance. Indeed the traditional definition of ‘alcoholism’ need not apply for there to be a productivity impact, as researchers from Norway found regular binge drinkers (five standard drinks or more in one sitting) were four times more likely to show a drop in productivity.

The problem is not uniform across sectors or populations although, generally speaking, male and young workers aged 14 -29 years, as well as individuals employed in certain industries (including lower-skilled and manual occupations, hospitality, mining, agriculture, retail, manufacturing, construction and financial services) were at higher risk of problematic drinking behaviours.

Pre-pandemic research found heightened risk from working under certain conditions such as in isolation away from friends and family; extended or shift-pattern working hours, in dangerous environments, under inadequate supervision or at risk from organisational change (restructure/redundancy)- a list that makes clear what may be driving this Covid related increase in consumption.

Resultant short-term absenteeism, reduced quality of work or output as well as the potential for accidents are not the only economic repercussions of problematic alcohol consumption. Staff turnover, with its associated loss of skills, cost of recruitment and training may all take a toll on our economic recovery.

Turning to mental health, the Centre for Mental Health reported that related problems at work cost the UK economy £34.9bn last year (up from £26 billion a decade ago) or the equivalent of £1,300 per UK worker. Similar to the effects of alcohol consumption, the bulk of this cost arises from workplace productivity loss rather than health systems or accidents resulting from mental health problems. Reduced productivity of those who are unwell but still at work- termed ‘presenteeism’, surprisingly incurs double the cost on businesses of absenteeism through sickness. Prior to the pandemic, one in five workers at any time would be in mental health difficulty. In the UK, anxiety, depression and stress alongside more serious mental health problems were the third largest cause of sick leave in 2015, accounting for approximately 17.6 million days’ absence, or an eighth of the total taken. Research by Oxford Economics found that over 180 thousand people were precluded from joining the labour force due to mental health problems.

While we cannot predict from the chart the exact scale of the impact, it is worth anticipating that the pandemic, the associated anxiety and fear or grief over lost loved ones will likely increase the challenges faced by employers in safeguarding the welfare of their staff.

The chief executive of the Centre for Mental Health, Sarah Hughes has said ‘Those employers that ignore the issue, or who undermine the mental health of their staff, risk not only the health of the people who work for them but the wealth of their business and the health of the economy as a whole.’.