Summary

With the hospitality sector in crisis, data from OpenTable shows that the number of people eating out in the UK is steadily increasing and has received a recent boost from the government’s ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme – although the numbers in London are still down over 50% on last year. In the US, the pace of the sector’s recovery has slowed markedly since June – with a third of restaurants still closed and volumes 51% below their pre-Covid level. As consumers become less cautious about going out and regain their sense of safety, the restaurant industry should gradually recover. However, the coronavirus crisis may also cause structural changes, which will result in long-term challenges for the hospitality sector as a whole. Given the importance of the industry to the UK economy, its ability to adapt to these challenges could have significant implications for employment and the pace of the economic recovery

What does the chart show?

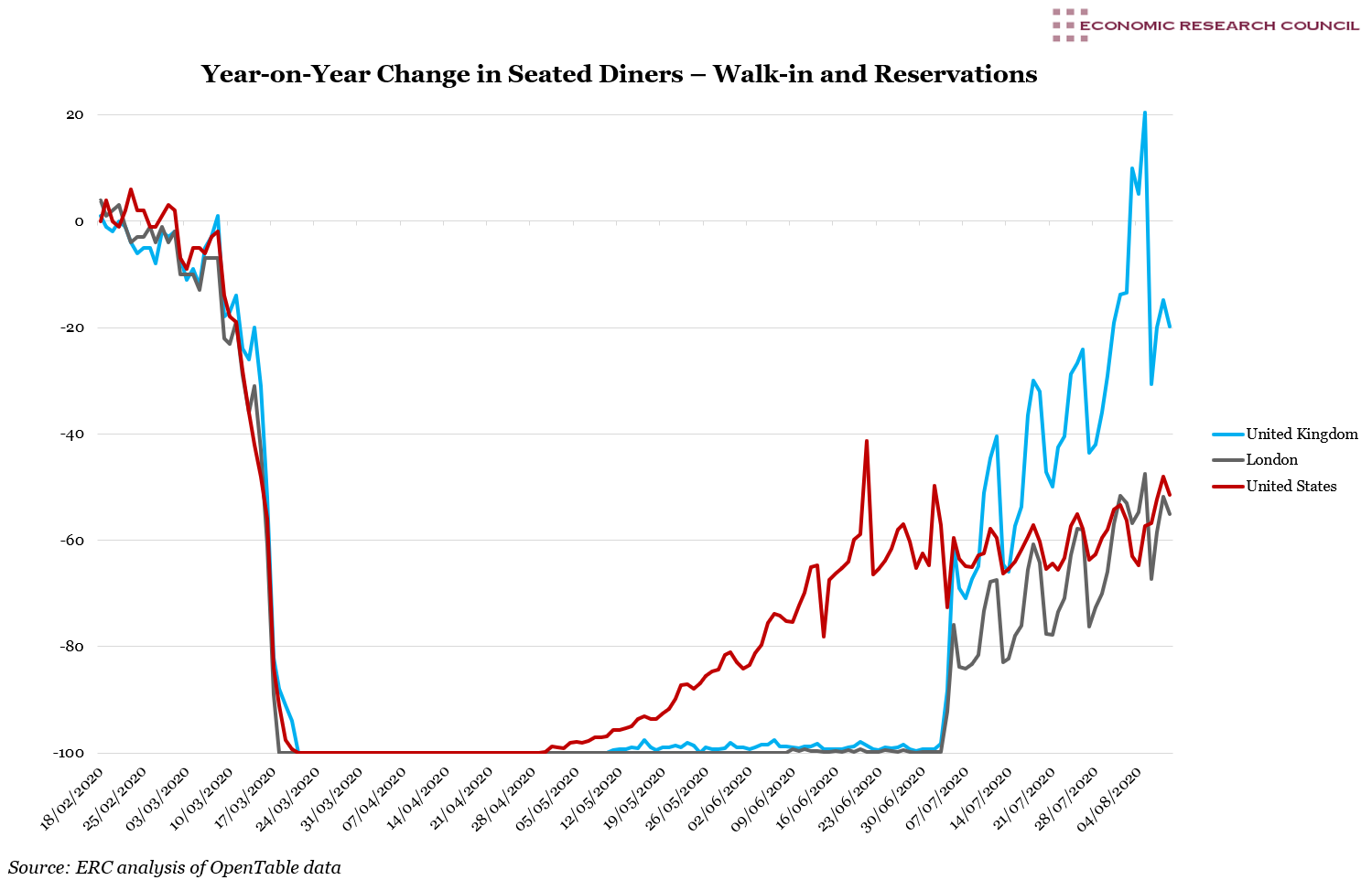

The chart displays the year-on-year percentage change in the number of restaurant diners, for each day from 18 February to 9 August 2020, the last point at which a complete week’s data was available. The blue line shows the data for the UK and the grey line, for London. The red line represents the data for the US, which has been included for comparison.

The data was collected by OpenTable, the online restaurant reservation company. It is drawn from a representative sample of 20,000 restaurants on its system and covers all modes of booking, including phone and online reservations and walk-ins. The year-on-year change is calculated by comparing the number of seated diners on the same day of the week in each year to avoid any inconsistencies caused by weekend trading – for example, Tuesday of week 11 in 2020 is compared to Tuesday of week 11 in 2019.

Why is the chart interesting?

The chart illustrates the dramatic impact on the UK restaurant sector of the government’s measures to control the spread of coronavirus, with the industry effectively shut down for a period of over 15 weeks. This sharp fall in activity was mirrored in the hospitality sector as a whole, with total revenues between April and June falling 87% year-on-year, from £34.2 billion to £4.6 billion, according to the trade association, UK Hospitality.

The chart also suggests that the path to recovery for restaurants may be a slow one. The government’s ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme – which runs on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays from 3rd to 31st August – clearly provided a boost to business in its first three days of operation. However, either side of these three days, visits were still down by around 20% in the UK, and 60% in London – with growth continuing to be held back by consumer cautiousness and new operating restrictions due to social distancing. The trend in the US also shows how vulnerable the sector is to a resurgence in coronavirus cases – where the number of seated diners appears to have plateaued at half its pre-Covid level, due to rising infection rates in several US states, with a third of restaurants still closed.

Perhaps more significantly, there are also likely to be some structural changes caused by the coronavirus crisis, which will create long-term challenges for the industry in the UK. First, some of the recent shifts in consumer behaviour may become permanent in certain demographic groups. In particular, while younger consumers are generally resilient, caution may persist among older customers. According to a YouGov survey in April, 29% of Britons say they will visit restaurants less frequently after the pandemic than before, and 11% much less than before. In addition, almost a third of consumers intend to spend more in their local neighbourhoods in future, based on a survey by GlobalData in May – and, according to another YouGov poll in April, roughly a third of those who used public transport pre-Covid will do so less in the future. These permanent changes in consumer behaviour suggest that people may be less willing to travel to restaurants, and may reduce the frequency of their visits, over the longer-term.

Second, companies and employees now recognise the benefits of remote working as a result of the crisis, and this is likely to lead to a permanent shift in working patterns. This will result in lower footfall in city centres, with many office workers continuing to work remotely for at least part of the week. According to the New West End Company, footfall in central London is still down over 60% year-on-year. Restaurants in urban locations, which rely on office workers and commuters for their trade, will therefore see a disproportionate impact on their sales – a trend already evidenced in the OpenTable data, which shows that the recovery in London is well behind the rest of the UK.

According to recent survey of employers by the CIPD, an association for HR professionals, 37% of staff are expected to work from home on a regular basis after the crisis, compared to just 18% who did so previously. Employers also expect the proportion of their staff working from home full-time to increase from 9% to 22%. This trend has significant implications for businesses that rely on regular footfall from office workers. Pret A Manger, the sandwich chain whose previous strategy was to ‘follow the skyscraper’, recently announced a restructuring of its entire business in response to these new trends. This involves the closure of 30 of its sites, the loss of over 1,000 jobs and a greater focus on its delivery operations.

Other companies in the hospitality sector will also need to adapt to changes in their business models as result of the crisis. Even when customers do return, social distancing requirements will reduce capacity – and hence revenue – in the medium-term, and perhaps for longer. In addition to the downward pressure on revenue, there will also be upward pressure on costs caused by new operating restrictions. For example, pub operators have seen higher labour costs due to the requirement to provide a table service as well as other new safety measures.

How successfully hospitality companies adapt to these long-term challenges could have a significant bearing on the pace of the UK’s economic recovery, given the importance of the sector to the country’s economy. According to research commissioned by UKHospitality, the industry generated over £72 billion of Gross Value Added in 2017. More recent statistics from the ONS show that the Accommodation and Food Services sector alone employs 1.8 million people, representing 5.4% of the UK’s workforce. Moreover, 43% of staff in this sector are currently on furlough according to the ONS’s latest Business Impact of Covid-19 Survey. When the furlough scheme ends on 31 October, there is clearly a risk that a large proportion of these workers will lose their jobs. A recent report by PwC suggested that 39% of furloughed workers in this sector are at risk of redundancy, four times higher than the next highest-risk sector.

The government fiscal stimulus targeted at the hospitality industry – in particular, the ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme and temporary cut in VAT – has provided a short-term boost to demand. However, it will not address the long-term challenges which the industry now faces, caused by the changes to its business model, and permanent shifts in consumer behaviour and working patterns. These challenges mean that hospitality companies will need to find ways to restructure their businesses to adapt to the ‘new normal’ if they are to maintain their profitability and, in some cases, if they are to survive.