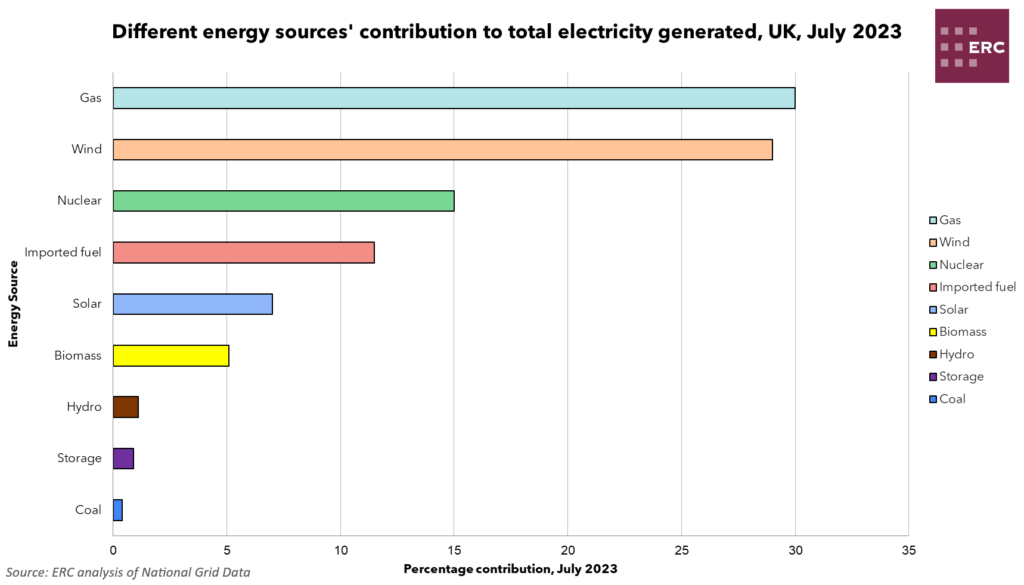

Summary

With energy as a key component in the heightened cost of living, the ongoing conflict in Europe has highlighted the importance of energy self-sufficiency; as new oil and gas licences cast doubt upon the UK’s commitment to net zero emissions by 2050, we explore the extent to which these are compatible with our climate pledges, and how this will likely impact household bills.

What does the chart show?

The chart shows the proportion of UK energy consumption driven by fossil fuels, since the 1960s, displaying the UK’s shift away from fossil fuels, which has accelerated over the past decade.

Why is the chart interesting?

At the end of July, PM Rishi Sunak announced plans to grant over 100 new gas and oil-field exploration licences before the next election; an apparent bid to strengthen British energy security, and insulate the UK from Russian “weaponisation of energy,” as put by the PM. This is despite factors that have deterred North Sea investment over recent years – including the energy windfall tax, and investors’ uncertainty over the fate of non-renewables within the net-zero transition – prompting over 90% of offshore energy companies to cut investment into the North Sea, according to OEUK. Notably, this has included Shell’s sale of their 30 per cent stake in the Cambo field – the second-largest undeveloped oil and gas discovery in the North Sea. In order to re-conjure investment, the headline rate of tax on oil and gas producers is expected to return from 75% to 40% by 2028, the rate applied prior to the Energy Profits Levy. The Energy Profits Levy however, has eased pressure on government finances, raising around £2.8bn to date, and is predicted to raise almost £26bn by March 2028, continuing to fund the cost of living measures such as the government’s Energy Price Guarantee. As such, this tax cut will occur only once prices have reached “historically normal levels for a sustained period,” as per Gareth Davies, Exchequer Secretary to the Treasury. Issuing UK firms new licences to drill in the North Sea could stabilise prices, if this allows us to ease reliance on imports – but what’s more; such policies which enable the operation of energy producers, preserve an estimated 215,000 jobs in associated industries, otherwise threatened by the UK’s mission to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

Issuing new exploration licences at all, however, seems to defy the UK’s principles of Building Back Greener, and decarbonising the economy. The PM has stated “Even when we’ve reached net zero in 2050, a quarter of our energy needs will come from oil and gas”, suggesting that the UK will ultimately only see a partial phase-out of fossil fuels. The chief strategy expected to mitigate additional emissions resulting from continued North Sea drilling is carbon capture and storage (CCS.) Despite the construction of two new CCS clusters, recently announced in the Humber and northeast Scotland, the technology is still in relative infancy, with CCS’ short track record in the UK proving poor. The first CCS project in the UK was proposed in 2005, though failed to secure funding in the required timescale. Negotiations for a new project fell through once again in 2007, and in 2015 the UK government retracted a proposed £1bn CCS competition – a further blow to investor confidence. Some have attributed the UK’s limited innovation in CCS technology to a lack of government-created incentives that support their improvement and commercialisation, as seen in the US – the world’s leader in CCS innovation. For example, awarding tax credits to firms developing CCS technology, or cutting duty on associated technologies relating to CCS development. The UK government propose that with sufficient development, CCS could not only help the UK achieve net zero but support up to 50,000 additional jobs too. Regardless of the argued potential for CCS’ implementation, MP Chris Skidmore, who led the government’s net-zero review, called this “precisely the wrong time”, to issue more drilling licences, placing the UK “on the wrong side of history”, with 2023 having witnessed numerous incidents of severe weather around the world.

In 2021, the UK produced around 50% of its own natural gas, via firms operating primarily in the North Sea. Of the other 50% imported, 77% arrived from Norway – for comparison, in the same year, just 4% of UK gas imports came from Russia. Norway is also the UK’s biggest source of oil, sending 11.7m tons in 2021, whilst only 2.7m tons came from Russia. Despite the UK not importing a great deal of fossil fuels from Russia directly, the UK achieving energy self-sufficiency remains paramount, as global fossil fuel prices are pushed up by declining Russian exports. The extent to which issuing new licences will actually contribute to protecting Britons from volatile global commodity markets is uncertain though. With the price paid for fuel at the pump closely linked to the global price of oil, many fear that new domestically-produced fossil fuels will be sold to the highest bidder on the global oil market, with the environmental and economic consequences ultimately shouldered by the public – a worry heightened by the total value of the UK’s fuel exports already increasing from £1.7bn to £4.1bn between April of 2020 and 2022. The UK’s capacity for gas storage furthermore contributes to current prices; whilst the EU can store over 100bcm of natural gas (enough to fulfil 1/3rd of EU demand during winter, and which is over 90% full ahead of this winter), the UK has the capacity for an unremarkable 2.5bcm of gas. This is equivalent to just 12 days of average demand.

With the conflict in Europe ongoing, the UK is just one nation pushed to bolster its energy supplies by whichever available means – however, whether further extraction of fossil fuels is the right move to budge prices, or whether technologies like CCS will be able to reconcile continued fossil fuel usage with emission reduction targets remains to be seen.

By Tyler Boruta