Summary

The UK is one of the least energy-efficient countries in Europe. Whilst efforts have been made to improve efficiency, they have often ended in failure. A coordinated and committed approach is needed to reduce reliance on fossil fuels, and lower household bills.

What does the chart show?

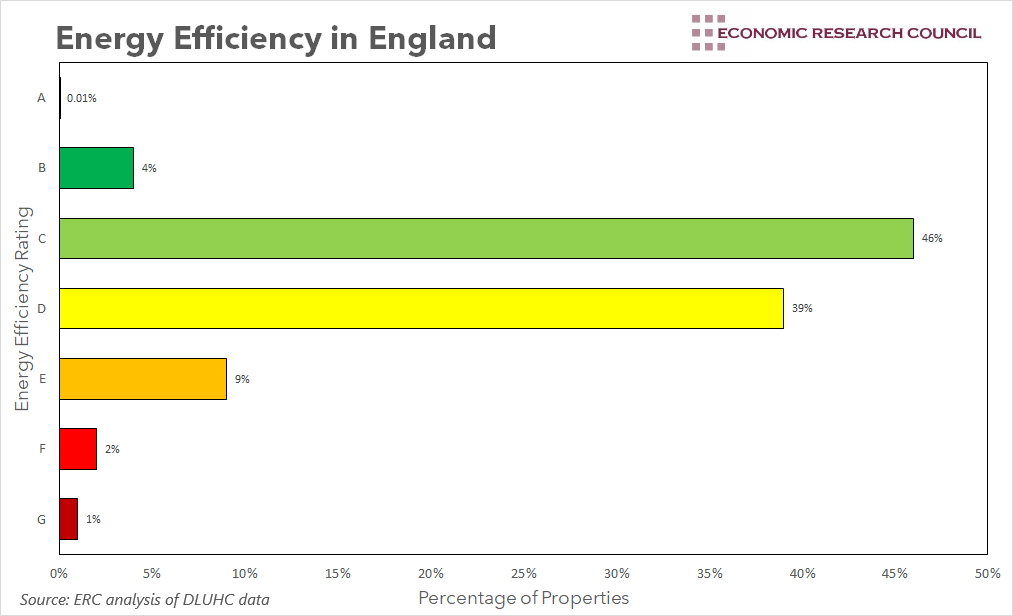

The chart above displays the proportion of existing dwellings that fall into each energy efficiency category, with A being the most efficient, and G the least efficient.

Why is the chart interesting?

As energy costs have soared through this year, many have considered ways in which they can reduce consumption to lower their bills. The government recently decided against running a public information campaign on energy use, but can more be done to improve energy efficiency in UK homes?

Energy Performance Certificates measure the energy efficiency of a building. The energy efficiency rating scores buildings between 1-100 and is dependent on the amount of energy used per square metre. The EPC provides a breakdown of the performance of each element of the building.

As the chart displays, 85% of homes in the UK fall into categories C and D for energy efficiency, with a score between 55 and 69 out of 100. Clearly, there is some room for improvement.

Energy efficiency ratings are impacted greatly by the type of housing. As housing stock varies considerably across the country, this is reflected in energy efficiency scores across England, with properties in London and the South East scoring the highest for energy efficiency. These areas tend to have a higher proportion of flats and new build properties, which tend to be more energy efficient.

Compared to the rest of Europe, however, the UK has a long way to go. The UK has one of the oldest housing stocks in Europe, meaning it starts from a relatively poor position. Most homes date back to pre-1990, before energy-efficient design became regulated. Around a quarter of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions come from the energy we use in our homes. The problem isn’t only with these older properties. Only 1.8% of newly built homes reach the highest standard of energy efficiency. In 2020, the share of renewable energy in heating and cooling for UK homes was just 8%, the second-lowest of all European nations.

Across the Channel, governments have made concerted efforts to improve residential energy efficiency. In the Netherlands, the ‘Energiesprong’ scheme uses prefabricated facades, insulated rooftops, smart heating, and ventilation/cooling installations to retrofit homes, making them net zero energy. These homes generate the total amount of energy needed for hot water, heating, and electrical appliances. Austria and Italy have both developed city-level refurbishment schemes to improve energy efficiency.

The UK unfortunately has less of a history of ground-breaking renovation schemes. David Cameron’s Green Deal planned to insulate 14m homes, however, only 2000 signed up before the scheme was wound up. Boris Johnson introduced the Green Homes Grant, a £1.5bn scheme that could be used on various efficiency-improving measures. The scheme was scrapped 6 months after its launch. More recently, however, the government has announced the Help to Heat scheme, providing £1.5bn to low-income households, allowing them to take measures to improve the efficiency of their homes.

The ongoing energy crisis has rightly shone a light on what can be done to reduce energy consumption and improve efficiency. Whilst many households will be taking steps towards this as we speak, coordinated efforts need to be made by governments to incentivise and promote energy efficiency. By doing this, we can reduce our reliance on fossil fuels, and lower energy bills in the long term.

By David Dike