Summary

We’ve gotten used to relatively cheap debt over the last decade, largely due to low interest rates and controlled inflation. Interest rates are rising, but importantly for today’s chart, so is inflationary pressure. As such, the interest payable on index-linked gilts has sky-rocketed and will continue to strain public finances if inflation is not addressed.

What does the chart show?

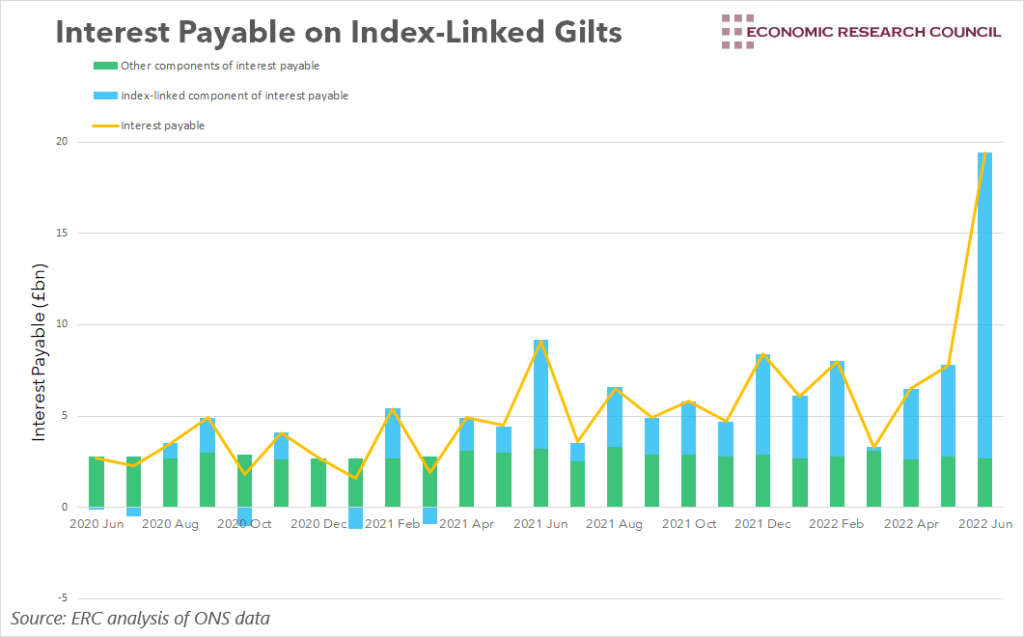

The chart shows the interest paid on UK government debt since June 2020. The yellow line represents the total interest payable, whilst the blue bars represent the portion of this interest that is linked to inflationary pressure, and the green bars represent other components of interest payable.

Why is the chart interesting?

It is sometimes suggested that running budget deficits and accruing government debt is somewhat more palatable during times of low interest rates, as these keep the cost of borrowing down. Successive increases in the Bank Rate have questioned the efficacy of this approach in recent months. Irrespective of this, a more subtle effect of inflationary pressure may provide even more of a reason to keep an eye on government debt.

When government spending exceeds government revenue, the difference is financed by selling gilts. Conventional gilts pay a fixed coupon payment every 6 months until maturity and account for roughly three-quarters of UK government debt. Index-linked gilts work similarly to conventional gilts, however the coupon payment, as well as the principal that is paid at maturity, move in line with the Retail Price Index measure of inflation.

This index link is not usually an issue. As the chart shows, prior to June 2021 when the index-linked uplift stood at a record level, the contribution of inflation to the total interest payable for index-linked gilts was relatively modest. However, as the inflation-linked portion of interest payable is calculated using three-month lagged RPI figures, this has become a bigger problem for the Treasury. The interest payable for June 2022 reflects RPI movement between March and April 2022, where the rise in prices stood at 11.1%. Throughout the entire period of analysis, the non-index-linked components of interest payable have remained stable.

Government debt is nothing new, and neither is the interest payable on this debt, but the values of June 2022 should be a stark warning to policymakers. £19.4bn was paid in interest alone. This is a staggering sum. To put it into context, the amount paid in interest in just one month was larger than the planned day-to-day spending of several government departments in 2021/22, including the Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities, the Department for Business, Energy, & Industrial Strategy as well as the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, who spent £3bn, £9.6bn, and £7.9bn respectively.

The magnitude of these interest payments put recent government policy, as well as policy proposals, into sharp focus. Public sector workers have recently been offered an average pay award of around 5%, with higher awards skewed towards lower earners. The IFS has estimated that this will cost the Treasury an additional £7bn above previous spending commitments, which will have to be found by expanding budgets, cost savings within departments, or both.

Looking to the future, tax cuts are the main story of the Conservative Party’s leadership race so far. Liz Truss has proposed reversing the planned NIC increase if she becomes Prime Minister. In addition to this, she has suggested that she will reverse the planned corporation tax rise. These measures are estimated to cost £13bn and £17bn per year respectively. Regardless of the politics behind public sector pay and tax cuts, what is abundantly clear is that the Treasury would have far greater fiscal headroom if it wasn’t paying £19.4bn in interest payments for index-linked gilts in a single month, £16.7bn of which is as a direct result of inflationary pressure. Inflation is predicted to be significantly above target well into next year. Interest payments on index-linked gilts are going to be a much larger threat to public finances than some spending decisions, accelerating the urgency with which inflationary pressure must be dealt with.

By David Dike