Summary

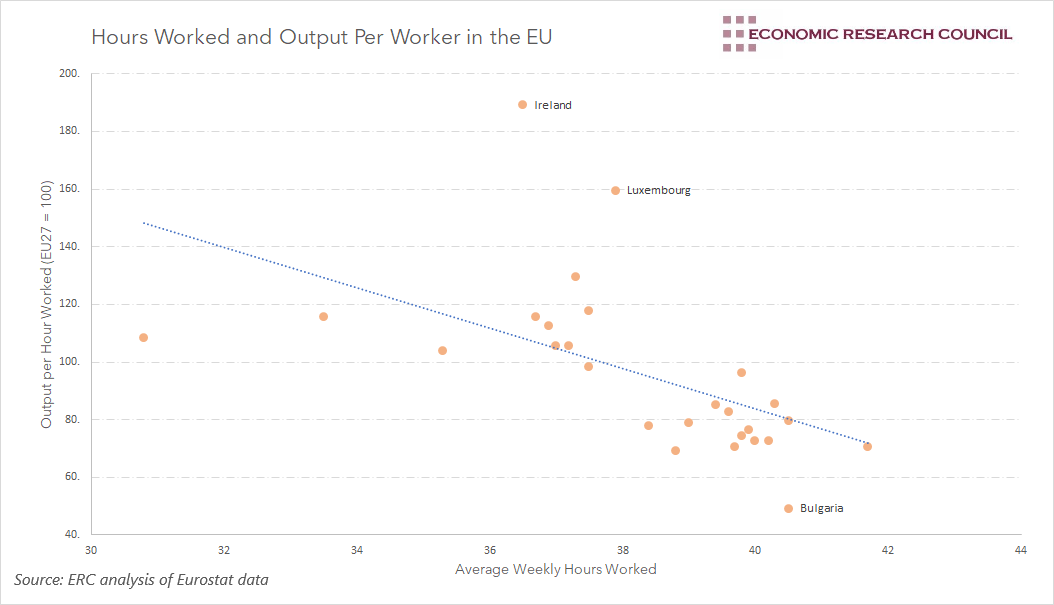

As a global 6-month trial begins to test the effect of shifting to a 4-day week, this week’s chart shows a strong negative correlation between hours worked and output per hour. Nevertheless, underlying factors seem to be driving this effect in at least some of the countries mentioned. As such, to drive productivity increases, we need to take into account the structural factors at play within nations.

What does the chart show?

The chart shows the relationship between the average number of hours worked per week, and output per hour worked, for all 27 EU countries in 2019. The measure of output used in this instance is GDP. The blue line indicates the line of best fit, portraying the negative correlation between the two variables.

Why is the chart interesting?

With over 3,000 UK workers undertaking a 4-day working week trial, the issue of the number of hours that people work, and its wider economic and social effect, has received much public attention in recent weeks. In fact, over 7,000 workers across 150 companies throughout the world have signed up for the 6-month, 4-day week trial, with many smaller trials already occurring in places such as Iceland, Spain and New Zealand. On the surface, the chart above provides some empirical backing to the ideas behind the trials, as a clear negative correlation exists between the average weekly hours worked, and output per hour worked, which is used as a proxy for productivity.

Proponents of the 4-day working week will not find this shocking. The most fundamental aspect of their argument suggests that as people work fewer hours in a week, this affords them more time to fulfil personal, social, and familial aims, allowing them to be more focused and productive when they are at work. As fewer hours worked per week is associated with higher productivity within European countries, this seems to provide weight to the 4-day working week campaign.

Despite this, correlation does not always mean causation, and assessing the intricacies of individual labour markets is necessary before reaching a conclusion. Good examples of this are the cases of Ireland and Luxembourg, countries with extraordinarily high productivity compared to the rest of the EU. Both countries are in the lower half in terms of hours worked but have levels of productivity over 50% above the EU average. In Ireland’s case, productivity levels are greatly inflated by the vast amount of multinational companies that have based their operations in Dublin and benefited from favourable conditions, despite output often being generated in other countries. Very similar explanations account for Luxembourg’s high level of productivity, in addition to its reliance on financial services.

Bulgaria, on the other hand, seems to epitomise the concerns of the 4-day week campaign. Bulgarians worked close to the longest hours in the EU in 2019 but achieved the lowest levels of productivity. Nevertheless, it seems that other factors may be at play. Challenges to the rule of law, and corruption, have long been cited as factors impeding investment in the country. Lack of investment has hampered the innovation necessary to spur productivity.

As such, simply relying on the correlation between hours worked and output per hour is not enough, as structural factors within each country will play a part. Nevertheless, at a micro level, there have been encouraging results from companies who have trialled a 4-day week. It clearly has the potential to revolutionise how society views work, but we have to move forward in a manner that balances the risks. Firstly, it is assumed that a reduction in working hours will increase productivity, allowing salaries to remain constant. Essentially, people will do the same amount of work in less time. It’s quite clear that this will be more challenging to achieve in some industries compared to others. For instance, it is very unlikely that a schoolteacher or healthcare worker will be able to increase their productivity enough to compensate them for the loss in hours worked. As such, more people will need to be employed, increasing costs in the private sector, and stretching public finances in the public sector.

The UK has typically fared poorly on national productivity ranking compared to major economies. It is unlikely that a 4-day week will be a silver bullet for us, especially as the campaign is gaining traction across the globe. We’ll need to think more broadly about organisational structures and other factors holding our productivity back. Nevertheless, the resurgence of the campaign serves to continue to offer hope to employees that have evaluated their relationship with work as a result of the pandemic.

By David Dike