Summary

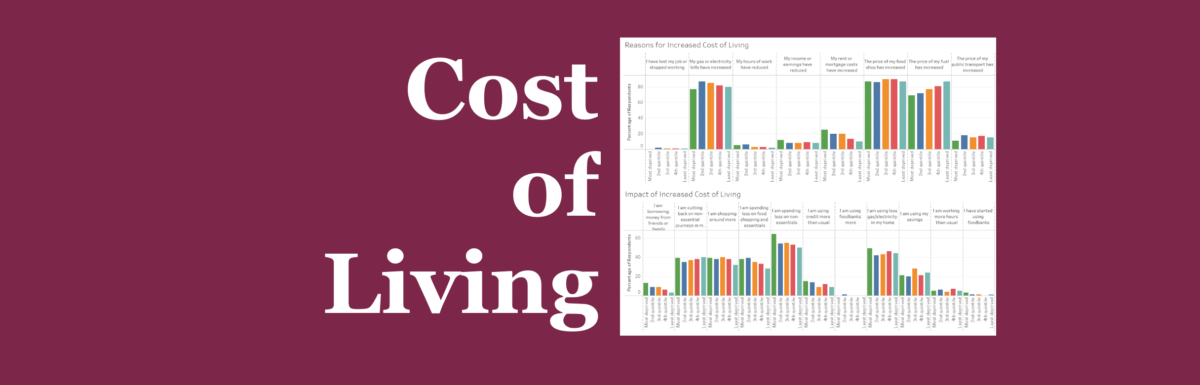

This week’s interactive chart looks at the reasons for, and impact of increases in the cost of living. Navigate through the chart above to explore the data.

What does the chart show?

The chart displays responses from the Opinions and Lifestyle Survey, conducted by the Office for National Statistics, between the 16th and 27th of March 2022. Responses are split between questions highlighting the reasons why people have faced increased costs of living and the impact that these increases have had. Respondents are grouped into quintiles based on the levels of deprivation experienced in their local areas. These levels of deprivation are calculated using the English Indices of Deprivation 2019, which ranks 32,844 small areas in England. Use the drop-down menus on the right-hand side of the dashboard to navigate the data.

Why is the chart interesting?

The rising cost of living has been much discussed in recent weeks, largely symbolised by ever-increasing inflation rates. This week’s chart seeks to understand the impact that this is having on the ground.

When assessing the reasons for increased costs of living, three factors stand out across all levels of deprivation. Increases in gas and electricity bills have squeezed people across the board, impacting 83% of respondents. This month saw a 54% increase in the energy price cap, causing havoc for many households’ finances. These higher energy costs have resulted in more people having difficulty paying household bills, with 23% of adults finding it either difficult or very difficult to pay bills in March. Comparatively, 17% of adults had the same issues in November 2021.

The most cited reason for increased costs of living was a rise in the price of food. 88% of respondents reported paying higher prices for their weekly shop. This has largely been caused by supply chain issues, shocks to supply due to the war in Ukraine, and rising raw material costs. Nevertheless, over 85% of people in each quintile of deprivation cite rising food prices as a key reason for increased costs of living, showing how widespread this problem is.

An increase in the price of fuel is the third most cited reason for increased costs of living, with 77% of respondents mentioning it as an issue. Crude oil prices have been rising since the onset of the pandemic, with sharper increases seen in recent months. The uncertainty caused by the invasion of Ukraine by one of the world’s largest oil producers has also put upward pressure on the price of oil. Nevertheless, the RAC has accused the bigger fuel retailer of profiteering, suggesting that “While the price of oil is still close to $100 a barrel, wholesale fuel prices don’t merit further retailer rises across the board at the pumps”. Interestingly, a clear trend exists in the proportion of people citing fuel prices as a reason for the increased cost of living, with people in less deprived areas experiencing this increase at a higher rate than people in more deprived areas. This simply occurs as more affluent households are more likely to own cars, as well as being more likely to own multiple cars.

Whilst the incidence is lower than the categories discussed above, rent/mortgage costs present an interesting point of analysis. The chart shows that people in deprived areas are 2.5 times more likely to cite rent or mortgage cost increases as a reason for increased costs of living. Less affluent households tend to spend a larger proportion of their income on housing, meaning increases in rental payments and mortgages affect them to a greater degree.

Whilst the reasons for increases in the cost of living are relatively clear to see and much discussed, the impacts give us more valuable information about how cost pressures have manifested in peoples’ lives, and the tangible effects they have.

By quite some distance, that largest effect of increasing cost pressure has been to reduce spending on non-essential goods, with 54 per cent of all respondents stating they had cut back in the area. By their nature, essential goods are assumed to be less sensitive to price changes, meaning non-essential goods are likely to experience more of a drop in demand when prices rise. Another interesting observation for this category, however, is the large difference between the most deprived and least deprived areas of the country. 64% of respondents in the most deprived parts of England have cut spending on non-essential goods, while only 50% have done the same in the least deprived parts of the country. As poorer people tend to spend a larger proportion of their income on essential goods, when the price of these essential goods increases, fewer funds are available to purchase non-essential goods, increasing the likelihood of them reducing spending in this area.

33% of respondents stated they were spending less on food and essentials, whilst 45% had decided to use less gas and electricity in their homes. These statistics combine to emphasise the mantra that many people are choosing between “heating and eating”.

By David Dike