Summary

With COP26 well underway, we analyse the efforts that developed countries have made in climate finance. Partly due to the potential impact of climate change on the nation, Japan leads the way in contributions. Over time, contributions have increased for each of the top 6 nations analysed, other than the United States. When assessing contributions as a percentage of GDP, the USA falls far behind other top contributors.

What does the chart show?

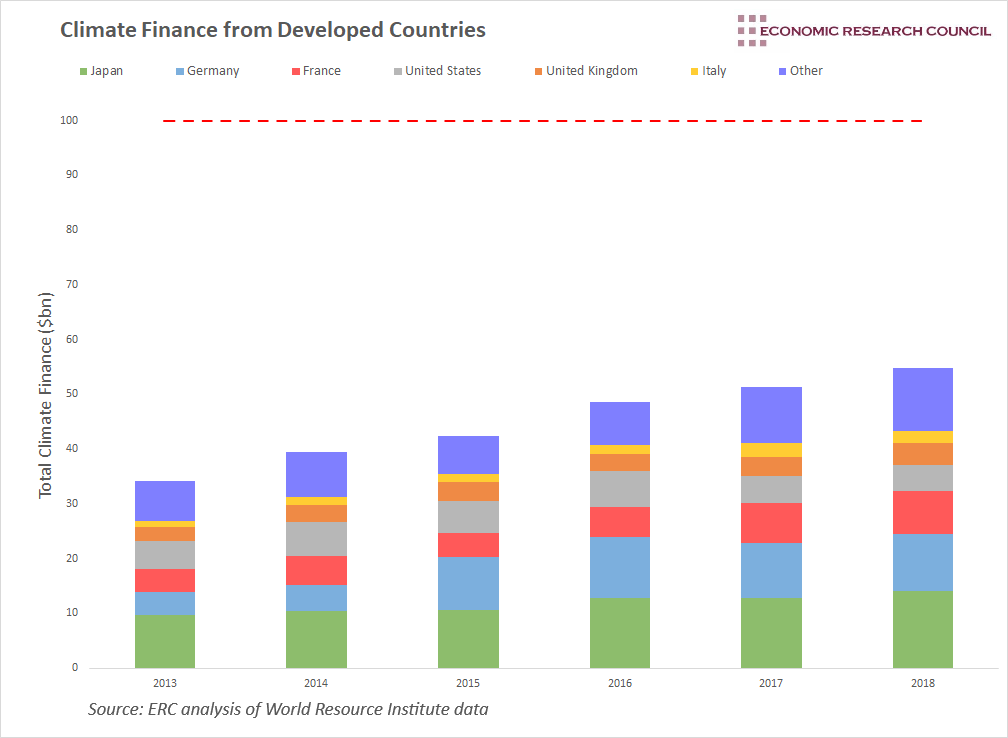

The chart displays the total attributed climate finance from developed countries, which includes bilateral climate finance and contributions to multilateral entities (including multilateral development banks). The chart includes data on 23 developed countries, defined by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

The bars for each year represent the cumulative climate finance outflows split by developed country. The top 6 contributors are detailed, with the remaining 17 falling into the ‘Other’ category. The chart displays data between 2013 and 2018 as official data for 2019 and 2020 will be available next year. The dashed line at the top of the chart displays the commitment from developed countries to mobilise $100bn per year by 2020, which was agreed upon at COP15 and formed part of the Copenhagen Accord in 2009.

Why is the chart interesting?

Climate change portrays the largest and clearest example of the tragedy of the commons known to man. Society, however, is continuously moving towards a point of realisation that efforts of some sort are needed to ensure the sustainability of our environment. Recent analysis by the Office for National Statistics has shown that concern for climate change within the UK population grew by 11% between 2012 and 2020, with over three-quarters of people saying they were concerned about the issue. The ongoing COP26 conference is further bringing matters to the attention of the public. A stated goal of the conference is to ‘mobilise finance’, restating the target of $100bn per year. This week’s chart, along with the restatement of the target, shows clearly that developed countries have failed in their climate finance aims.

The chart shows that Japan has consistently led the climate finance efforts of developed countries. Japan has contributed over $10bn every year since 2014, with its 2013 contribution being marginally below this figure. Nevertheless, in 2013 they contributed over twice the amount of any other developed country. Japan’s contributions have risen every year, culminating at $14.1bn in 2018. Their island geography potentially plays a part in their mobilization of climate finance, as rising sea levels constitute a pertinent threat for the country. As COP26 got underway, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida pledged a further $10bn in climate finance over the next 5 years, on top of $60bn already pledged.

Germany has significantly increased its climate finance efforts throughout the period of analysis, from $4.1bn in 2013 to $10.3bn. It is now the 2nd highest contributor of climate finance. Out of the 23 countries, Germany’s increase is second only to that of Iceland, which increased their contributions by a scale of 1.75 over the period. The UK has also experienced a steady rise, almost doubling contributions between 2013 and 2018.

The United States is the only country out of the top 6 to reduce its contributions, and only one of two countries within the 23 (the other being Norway) to do so. It peaked at $6.6bn in 2016, but fell to $4.7bn by 2018, coinciding with the premiership of Donald Trump.

Assessing these figures as a percentage of GDP presents further insights into the relative importance that nations place on climate finance. Of the 6 largest contributors, France, Germany, and Japan led the way, with 0.29%, 0.28%, and 0.26% of GDP spent on climate finance in 2018. Britain and Italy are some way behind, with 0.14% and 0.11% respectively, but this is a great deal more than the 0.02% contributed by the United States.

The 2018 figures came at a time where the President of the United States was relatively isolationist, and somewhat sceptic of the necessity to address climate change. The new administration is likely to mean these figures reverse, especially as Joe Biden has returned the United States to the Paris Climate Accord and has been more vocal on the role that the USA can play in addressing climate change. This year, he announced the USA would pursue a 50-52% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, compared to 2005 levels.

Rather than the bars, the most striking aspect of the chart is the white space above it. Developed countries didn’t even manage to reach half of their target until 2018. Whilst analysis of more recent data will be useful, efforts to address the pandemic are likely to have impacted nations’ ability to spend on climate finance. Nevertheless, developing countries will need to see a concerted effort to reach the $100bn target if efforts to tackle climate change are to be seen as credible. For them, observing developed countries fail to pay to remedy environmental degradation after reaping its rewards post industrialisation will completely devalue collective efforts to address climate change.

By David Dike