Summary

Whilst children have largely been spared from the medical effect of COVID-19, they have faced significant disruption to their education. This has been profound for primary school pupils, although the effect for secondary school students has also been significant. The average figures presented in this analysis are unlikely to be relevant to any individual, as the extent of remote learning has differed significantly. The analysis also shows the disproportionate effect that remote learning has had on more disadvantaged students. Schools and policymakers therefore cannot take a broad-brush approach in rectifying the issues associated with remote learning.

What does the chart show?

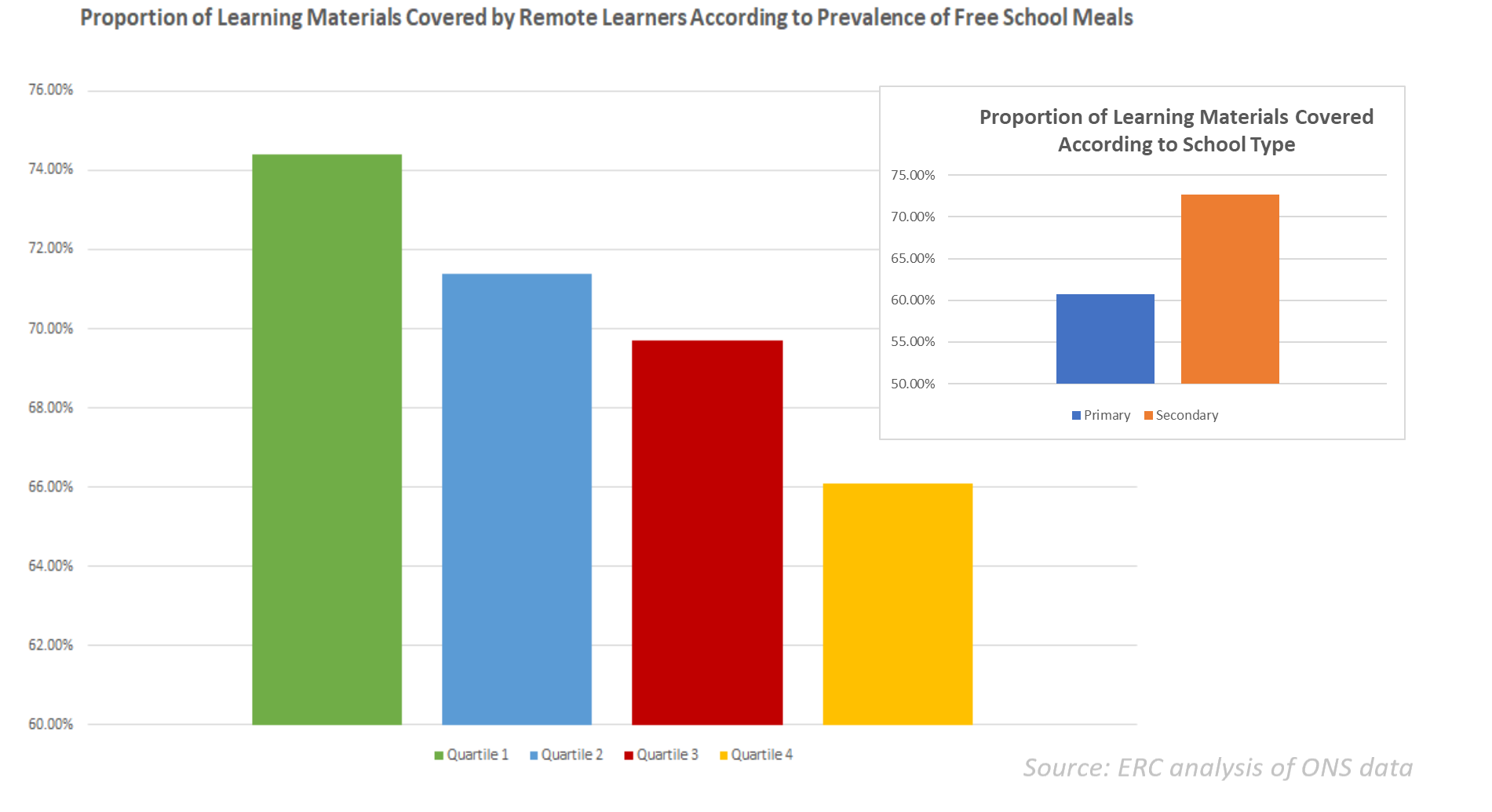

The chart displays the proportion of topics covered in school by remote learners as a proportion of the topics covered by children that attended school. The data is split by the prevalence of children eligible for free school meals. Quartile 1 represents schools with the lowest proportion of free school meals eligibility, whilst quartile 4 includes schools with the highest proportion of free school meals eligibility. The smaller chart also displays the proportion of topics covered by remote learners, comparing primary and secondary schools.

Why is the chart interesting?

The pandemic caused incredible disruption to children’s learning as schools scrambled to educate students in their homes. Even as national lockdowns ended, a large number of students logged into remote lessons, or completed independent work at home, due to outbreaks in schools and year groups. The majority, if not all students have felt a significant impact on their learning since the start of the pandemic. What has been less clear, however, is the magnitude of this impact. The chart above sheds some light on those that have been hit the hardest.

Addressing the smaller chart above, the data clearly shows that overall, primary school pupils have had a more significant impact on their education than secondary school pupils. On average, between April 2020 and June 2021, primary school pupils who learnt remotely only covered 61% of the content they would have covered in school, compared to 73% for secondary school pupils. In addition to this, as to be expected, primary school pupils were more dependent on parental involvement when learning remotely. This helps to explain the difference in content coverage, as more independent secondary school pupils were able to get on with their education with less assistance from parents, who may also have been working remotely.

The greater content coverage of secondary school students may seem promising at first, however, this still leaves a schism between what has been covered and what should have been. Secondary school pupils who learnt remotely missed out on over a quarter of their education between the first lockdown and the end of the last academic year.

A word of caution should be noted when assessing this data, however. It takes an average based on each month up to June 2021, excluding holiday periods. National lockdowns and school closures only take up part of this time, meaning the majority of students were educated in school during parts of this period. Where most students were in school, students who were educated remotely would have either tested positive for coronavirus, were in contact with a positive case, or were shielding. This presents a wide variance in terms of the total time an individual could have been learning remotely, with some only learning remotely when schools were ordered to close, and others spending a significantly higher proportion of their time at home due to the reasons stated above. This is the crucial problem facing schools and policymakers. The chart shows that primary schools need to have provisions and resources in place to ensure that students catch up to an acceptable standard before starting secondary school, but the more challenging issue is how schools can identify and support those students who have disproportionately engaged in remote learning.

The number of children on free school meals rose to 1.7 million in early 2021. Much has been discussed on the supply of these meals, with Marcus Rashford leading a charge to extend their provision. The chart above shows how the uptake of free school meals, a useful proxy for the level of disadvantage, has interacted with outcomes of remote learning. Quartile one represents the schools with the smallest proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals, whilst quartile four include schools with the highest proportion. We see a clear negative correlation between free school meal eligibility and content covered in remote learning, where schools with the smallest proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals covered over 74% of the content, and schools with the highest eligibility only covered 66% of the content.

Several factors can explain this phenomenon. Firstly, where free school meal eligibility is low, teachers are more able to utilise technology that pupils have access to. The National Foundation for Education Research found that the proportion of students with little to no access to IT in deprived areas was twice that of affluent areas. In addition to this, societal issues that can be linked with a greater prevalence of free school meal eligibility tend to have a greater impact on students when learning remotely compared to in school. School can be a haven for some students, and the removal of that safety net will not only have impacted educational attainment but personal and social factors as well.

The path forward is a complex one to navigate. Schools are no doubt getting to grips with the challenges associated with 2 academic years of disruption and implementing plans to bring students up to speed. For these to be effective, forensic analysis of the needs of individual students is required. In addition, a concerted effort is needed from policymakers to ensure that resources are directed appropriately to the schools that require them the most. This can only take a bottom-up approach, directed by educational establishments who understand the specific needs of their cohorts, and the challenges they have faced thus far.

By David Dike