Summary

The days of eyewatering profits in football appear to be over. Unlike other businesses in the entertainment sector, football clubs are burdened with astronomical fixed costs of stadia, extremely high wages and transfer instalments, alongside plummeting broadcast seasonal revenues and matchday earnings. Domestic broadcasters anticipate at least £300 million in losses on the next season, and the crisis conversion of the Champions League to single-leg fixtures will cause additional damage to big clubs’ balance sheets. While the ‘Big Six’ clubs, supported by extremely wealthy owners and big official partners may be able to weather the storm, many middle-table clubs and promoted teams will fare worse. The cumulative effect of previously high debt and other accounting problems have, via the pandemic, been drawn into sharp relief. Under normal circumstances, the transfer market could offer such clubs a lifeline via inflated prices for players sold to richer clubs. However, this prospect has been scuppered (at least for this season) by the pandemic, particularly for bottom-up trade-offs.

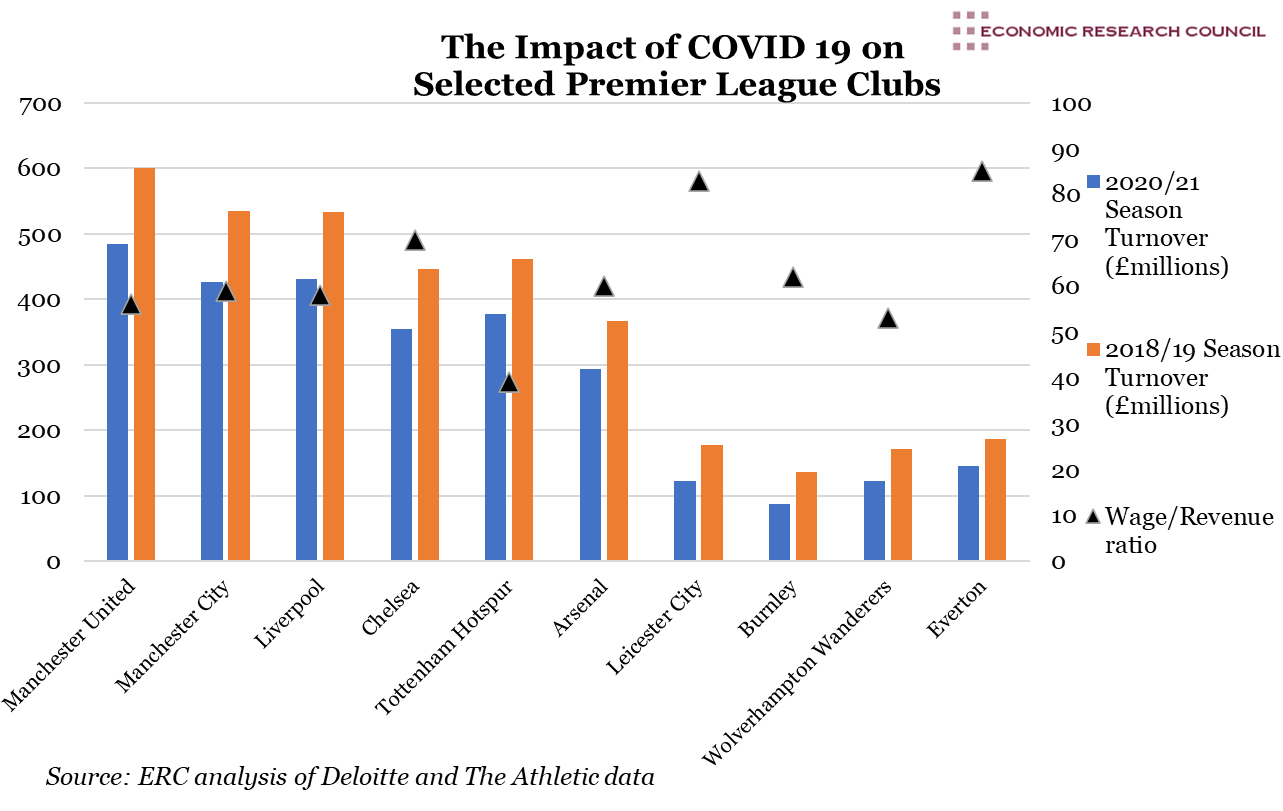

In this context, the chart compares the turnover of the premier league clubs before and during the pandemic, illustrating their catastrophic financial position and the challenges they must surmount.

What does the chart show?

The chart displays the turnover (in £ millions) of the ten clubs with the best performance, measured against the left hand axis. Turnover for the 2018/19 season is shown by the orange bars, and for predictions for the 2020/21 season, blue bars are used. The turnover data was collected from and article in The Athletic: The ‘terrible’ state of Premier League clubs’ finances.

The black triangles (measured against the right hand axis) represent the clubs’ wage/revenue ratio for the 2018/19 season, originating from Annual Review of Football report issued in June 2020 by Deloitte. The higher the ratio, the more club revenue is spent on wages.

Why is the chart interesting?

Most-watched globally, to some extent the Premier League has been financially shielded thanks to national and international broadcasting rights, that would have totalled £5.25 billion for the 2020/21 season. Resuming play on the 17th June has heartened many, who hope that, as long as the ball keeps rolling, money will keep circulating. However, the protection offered by big partners will become increasingly critical. With sponsors such as Chevrolet, Adidas, DHL, Etihad, Nissan and EA sports etc, it is clear that many of these firms are indeed suffering their own crises, with attendant effects on the clubs they support. For middle-table and lower teams, the pandemic will provide an impetus to keep themselves in more stable financial shape. In the future, advocates of a game less driven by money hope that the crisis could curtail the competition among clubs to lavish exorbitant sums on their players, perhaps engendering reforms like salary caps.

As one of the most successful business in the world with big flows of capital, football has allowed the development of somewhat artificial management habits inside the top clubs in leagues. A prime example is the wage spend- ranging from 55% to 88% of the displayed club revenue. This peculiar business practice has been justified by a Spearman’s rank calculation by Deloitte, quantifying the relationship between wages, spending and league position. This has proved that higher wage spending results in higher league performance, creating a reinforcing cycle where the leading teams seek to pay players ever-mounting salaries, and smaller/ less successful clubs compounding this with the inflation of saleable players’ salaries. This system has hitherto been propped up by an almost circular system, where most premier league clubs receive over around 60% of their income via broadcasting rights, only to spend around the same amount on footballers’ salaries and transfer instalments.

Previously criticised for being of little benefit to their local economies, in the aftermath of the crisis football clubs’ local economic impact is likely to diminish further. Most managers remain occupied with their club negotiations about pay cuts of around 20% to 30% for most of their footballers, an initiative they cite as a means to avoid using government funds to furlough non-football staff and a way of generating funding for NHS Charities. Premier League clubs have attempted to counter criticism and support the fight against Covid by offering stadia for NHS treatment and offering accommodation (for example the Chelsea Millennium Hotel). Players have responded with individual voluntary NHS fundraising via initiatives including #PlayersTogether. However, some players have become outspoken defenders of their wages, for example Wayne Rooney, who decried that ‘footballers [are] suddenly the scapegoats’ continuing that ‘[If] Manchester United or Man City need 30 per cent of their players’ wages to survive… then football is in a far worse position than any of us imagined.’. He may be correct that the clubs’ need to make financial savings are not the primary driver of such measures, however their reading of the public mood may be more sympathetic than his.