Summary

The 2021 census revealed that over 22% of families live with at least one “adult child” – a single, childless person aged over 18. This, and record low rates of mortgage borrowing, reflect the impacts of the cost of living crisis – specifically upon aspiring home buyers and renters. In this chart, we explore the extent to which the UK housing crisis is a matter of supply, and how recent plans – concerned with increasing housing density in urban areas – might resolve this.

What does the chart show?

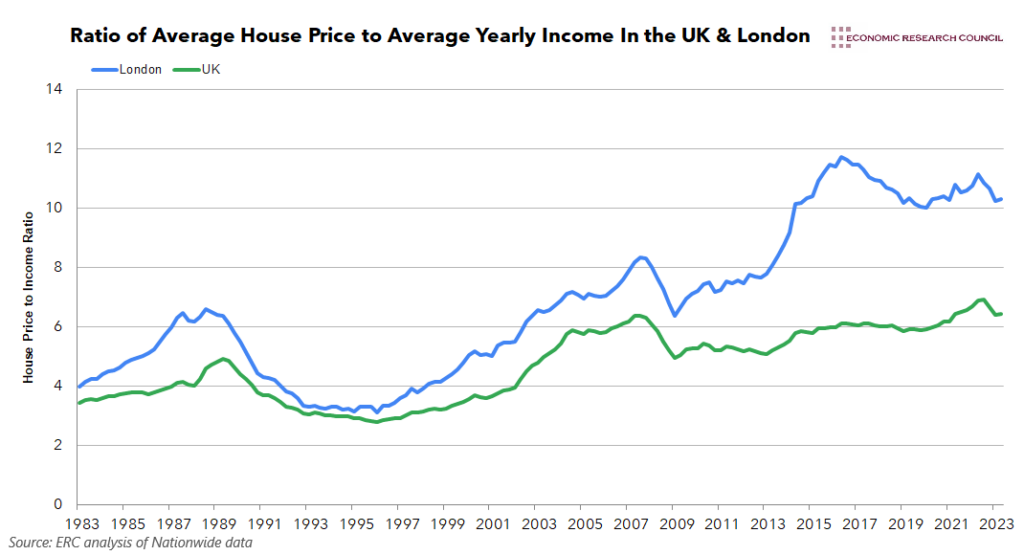

In Q3 2022, the average price of housing in the UK reached an all-time high, and despite slightly easing in recent months, renting – let alone buying a home – is unattainable for many. The chart shows Nationwide Building Society’s data for the ratio of average yearly incomes to average house prices, over time. It displays that house prices in the UK, on average, have gone from below 4x the average yearly income, in 1983, to more than 6x the average yearly income today – and more than 10x the average yearly income in the capital.

Why is the chart interesting?

As per the most recent census data, the adult population in England increased by 3.1 million between 2011 and 2021, creating demand for an estimated 2 million additional homes. Only 1.4 million homes were constructed in this period, though. The UK’s housing crisis is, in part, a supply-side issue – and the government recognises this. Secretary of State for Levelling up, Housing & Communities, Michael Gove, has renewed his commitment to the manifesto pledge of 300K new homes built yearly, by the mid-2020s; despite the Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Committee evaluating this as “impossible to achieve.” Nonetheless, at the end of July, the Prime Minister, in conjunction with Gove, confirmed that 1,000,000 new homes would be constructed by the end of this parliament – two recent announcements, in particular, reveal how the government plans to increase the UK’s housing stock by such a degree.

Firstly, a relaxation of the rules regarding property extensions and loft conversions – so that as families grow, their homes aren’t as restricted from growing with them, ideally reducing demand for – and the price of – new homes. Alongside this, greater freedoms have been granted to business owners looking to convert their retail spaces into rentable housing, as Gove argues that the UK must “make better use of the buildings we already have.” Notably, both of these announced changes focus on increasing housing density within existing urban areas, rather than encouraging further urban sprawl, or encroachment into rural communities. This has raised questions about the justification for the Metropolitan Green Belt – an area 3x the size of London, which encircles the capital. Purported to protect the UK’s ecology, while encouraging intensified usage of existing urban areas, some argue that it serves only to keep housing prices up in London, perpetuating rural NIMBYism. The Adam Smith Institute claim that the majority of the London green belt is “not environmentally valuable at all” on account of largely being comprised of intensively-farmed agricultural land – and just 3.7% of this could be converted into 1,000,000 homes – conveniently located where they are needed the most. At the same time, this presents a small-scale environmental opportunity of its own, as greater housing stock can result in a greater number of residential gardens and parks. However, expressing support for such policies can make it difficult for MPs to garner support among their home-owning constituents who benefit from high house prices. Furthermore, the continued allowance of London’s expansion would defy the principles of levelling up and ongoing efforts to shift the UK’s economic centre of mass away from the capital.

Secondly, the government also announced the £24m Planning Skills Delivery Fund; allocated to clear out existing backlogs in UK house-building (largely resulting from the post-COVID spike in the number of planning applications) and to equip local authorities with the skills necessary to deliver the changes set out in the Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill. Hence, the “super squad” of leading planners, selected by the government, to direct this project – it involves twenty zones across the UK, not including London, designated for new home developments – an idea initially proposed in the Levelling Up the UK White Paper released in February of last year. The first of these zones being “supercharged”, as Gove put it, is Cambridge; despite being the home of a world-class university, and over 3,000 information technology firms, eager to secure the town’s graduates, the region’s prosperity is limited by its housing stock (as well as limited laboratory spaces). Dwindling spaces for graduates to live and work in are hampering the region’s potential for employment in advanced sectors, as average property prices stand at almost £600,000; more than twice the UK median. Despite this scheme’s potential to improve housing conditions for those in Cambridge, and expand the UK’s science & technology sector, it is threatened by a formal objection from the Environment Agency and local MPs, citing fears around the town’s unsustainable water supply.

The cost of housing is not solely a result of too few homes being built, however. The Monetary Policy Committee’s most recent – and 13th consecutive – hike in the base rate, has ballooned the cost of mortgage repayments (and rents for those living in buy-to-let properties) significantly. In just the 12 months to December 2022, the cost of a new mortgage, on an average semi-detached property in the UK, rose by 61%. Furthermore, the UK’s pool of construction workers – vital in meeting our house-building targets – is extremely limited. These labour shortages are of such intensity that they prompted the government’s recent relaxation of visa restrictions upon bricklayers, roofers, carpenters and plasterers to name just a few occupations. A final contributor to the cost of housing, particularly in the capital, is the incidence of non-primary residences. The total value of the staggering 87,000 vacant homes in London equals over £130bn – for comparison, Bournemouth followed London with the 2nd-most vacant homes – only 7,200, at a mere value of just under £3bn. This highlights that such exceptional rates of home vacancy are not a UK-wide issue, but a symptom of London – as a global city, with almost a quarter of a million properties owned by foreign investors.

By Tyler Boruta