Summary

When faced with the prospect of rising interest rates, some have dismissed the potential pain it will cause by arguing that rates were much higher in the 80s and 90s. This week’s chart compares the impact on living standards that high mortgage rates had on homeowners in the late 80s to the present day, explaining that high rates in current housing market conditions could have a detrimental effect on consumption.

What does the chart show?

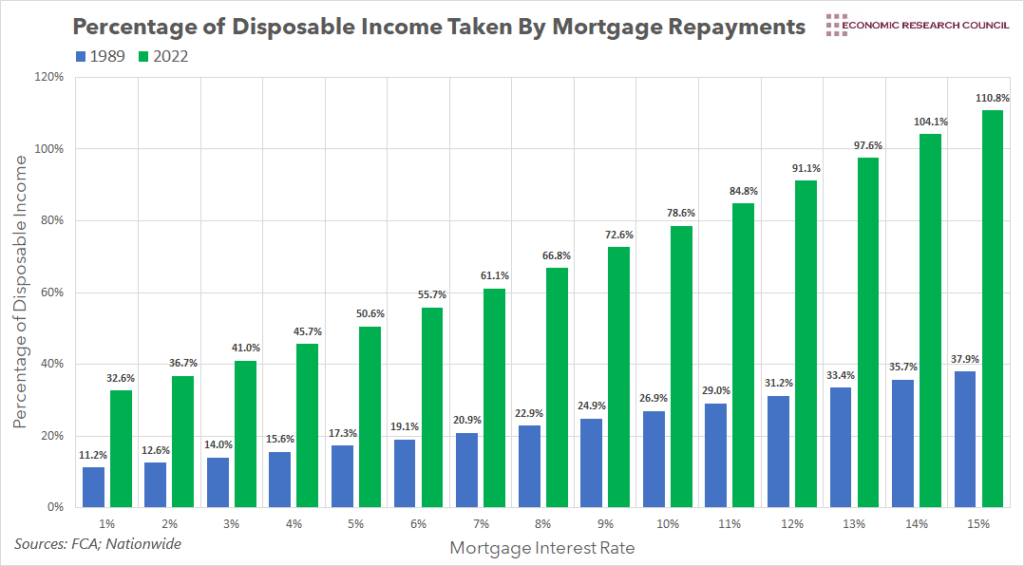

The chart displays the proportion of household disposable income that is taken up by mortgage repayments depending on the mortgage interest rate. The blue bars represent this proportion for homeowners in 1989, who bought an average-priced property and earned the average income. The green bars represent the same concept, but for homeowners in 2022. All analysis is based on an 80% loan-to-value.

Why is the chart interesting?

The Chancellor’s mini-budget brought a reduction in stamp duty that much had welcomed, but other factors seemed to have a greater impact on the medium-term trajectory of the housing market. His extensive reductions in taxation, coupled with the increase in borrowing required to fund them, and his side-stepping of the Office for Budget Responsibility spooked the markets and led interest rate expectations to rise to a high of over 6%. To say the Chancellor is entirely at fault for such high-interest rate expectations would be disingenuous. The Bank Rate has risen in every MPC meeting since it stood at historic lows in December last year. Meanwhile, the Bank of England has made it clear that they’ll be willing to raise rates further to combat inflationary pressure. These factors have all led to a mild sense of panic in the housing market, as interest rates on new mortgage products have risen to reflect circumstances in the market.

Haven’t we just gone through a period of historically low interest rates? Surely some adjustment upwards is bearable? On the surface, these assertions seem feasible. Interest rates are starting to creep up but are nowhere near the rates seen in parts of the 20th century. This argument misses a crucial point, however. The ability to repay mortgage debt depends on a lot more than the rate of interest.

The proportion of disposable income spent on mortgage repayments for first-time buyers is at a similar level to that seen in the late 1980s/early 1990s, though not yet at the peak of the period. Since the early period of the pandemic, this proportion has been rising, with the average first-time buyer now spending almost 35% of their disposable income on their mortgage. The situation is worse for those in London, who on average spend over 55% of their disposable income on mortgage payments.

The situation described above may seem a little concerning, though not unprecedented. After all, first-time buyers in the UK spent almost 50% of their disposable income on mortgage payments in 1989, whilst the figure stood at almost 80% for those in London. Crucially though, we experienced far different circumstances in the housing market then, compared to now. Firstly, between May 1988 and October 1989, the Bank Rate more than doubled from 7.38% to 14.88%. Secondly, house prices are vastly higher than they were in the 80s and 90s. The following analysis serves to compare the impact of interest rate rises between the late 80s and now.

At the end of 1989, average house prices stood at around £60,700. Moving from paying a rate of 8% to 15% would have cost the average household an additional £250 per month, increasing the proportion of disposable income spent on mortgage payments from 23% to 38%. Moving forward to the present day, average house prices across the UK stand at £282,800. The average mortgage interest rate in Q2 2022 was just over 2%. This means that the average UK household spent around £960 per month on mortgage repayments, amounting to 37% of their disposable income. We’ve gone through a sustained period of low interest rates, with rates only starting to rise in recent months, yet the average household was spending nearly the same proportion of their disposable income on mortgage payments as they were during the late 80s peak.

Since last week, markets have lowered their interest rate expectations from over 6% to between 5.5% and 5.75%. Moving from paying 2% to 5.5% will cost the average family an additional £431 per month, and increase the proportion of disposable income spent on mortgage payments to 53%. Whilst it may be manageable for some, it will not be for others, and further increases in interest rates will soon be completely unaffordable for many. Hypothetically, if rates increased to levels seen in the late 80s, the average family in the average home would spend almost £3000 per month on mortgage payments, more than their entire disposable income.

Whilst our focus has been on average families, rises in interest rates will hit some harder than others. Londoners tend to spend a larger proportion of their disposable income on housing compared to people in other parts of the country, and so will feel more of an impact when they come to re-mortgage. Secondly, more recent buyers are adversely affected compared to those who have owned their homes for many years, simply due to the fact that they have had less time to pay off their mortgage debt.

Whilst certain calculations have been simplified for ease of analysis, the above serves to dispel the notion that a substantial increase in the Bank Rate could be palatable, as rates are lower than they were in the 80s and 90s. Two factors are largely at play here. Firstly, the price of housing is much higher than it was, meaning most people must take out far larger loans than they would have done in the past. Secondly, wage growth has been significantly outpaced by the growth in house prices, meaning a greater proportion of households’ income is used to service mortgage payments. Significant increases to the Bank Rate filtering through to increases in mortgage rates will erode households’ disposable income to the extent that they will be forced to reduce spending elsewhere. Coupled with the cost of living crisis, it has the potential to grind consumption to a halt for the 6.8 million people in the UK who own their property with a mortgage.