Summary

Auto-enrolment is one of those policies that are very hard to argue against. It had the foresight to address a problem that forthcoming generations will experience, whilst simultaneously easing the burden of the future state. This week’s chart assesses its impact, as well as potential improvements we may see in the future.

What does the chart show?

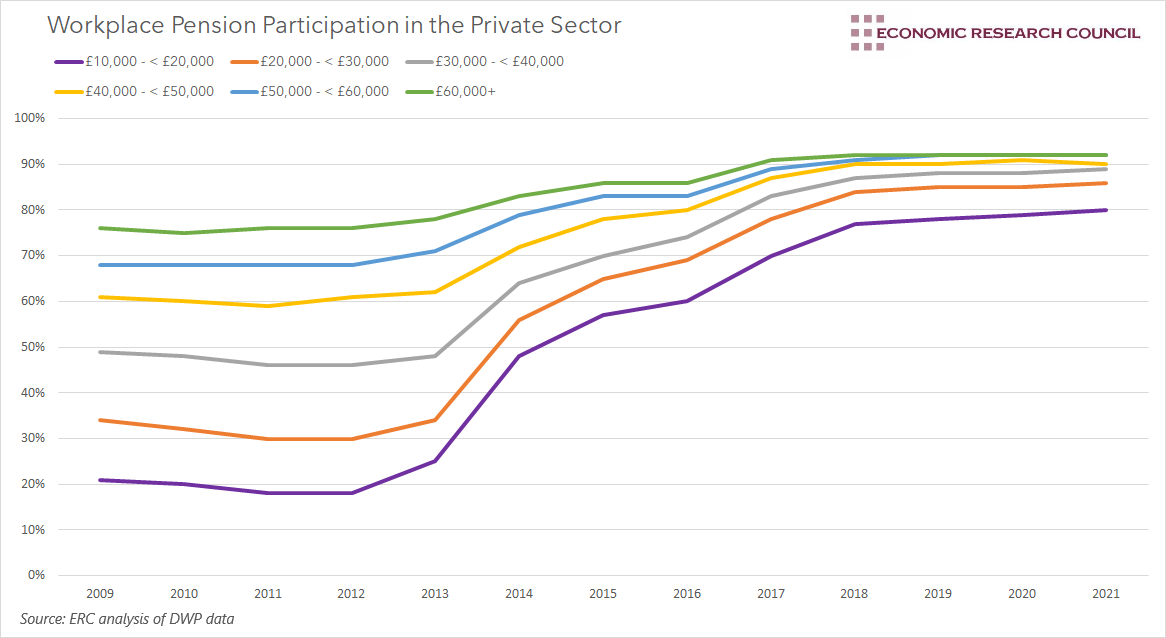

The chart displays changes in workplace pension participation rates of employees eligible for auto-enrolment in the private sector. Each line represents a specific income band.

Why is the chart interesting?

In 2012, the government amended how employees enrol for workplace pensions, shifting from an opt-in to an opt-out system. The policy aimed to simultaneously reduce the number of people that would retire and only receive the state pension, and to reduce the number of people facing inadequate retirement income despite having a private pension.

Workplace pension participation has traditionally been high in the public sector, with 89% of eligible workers enrolled in a scheme in 2009, compared to 45% in the private sector. In addition to this, while public sector enrolment increased in the two decades leading up to 2010, pension participation among private-sector workers decreased over this period and had been on a downward trajectory since the 1960s. As such it is clear that private-sector employees were the main targets of auto-enrolment.

When assessing private sector participation rates across income bands, it is clear to see that lower earners experienced far lower levels of workplace pension participation compared to their higher-earning colleagues. In 2009, the difference in participation between those earning over £60k, and the lowest earners eligible for auto-enrolment stood at 55%. By 2021, this had shrunk to only 12%, highlighting the strong success of the policy. Furthermore, through this period, participation rates among higher earners have not simply remained static. Whilst participation of the lowest eligible earners increased by 59%, participation amongst the highest earners increased by 16%. As the chart shows, auto-enrolment has significantly impacted the number of private-sector employers saving in a workplace pension across the whole income distribution, with 45% of all eligible private sector employees participating in 2009, compared to 86% in 2021.

Looking more broadly, since 2012 when auto-enrolment was implemented, participation rates among all eligible workers grew from 56% to 87% in 2021. Perhaps more interestingly, participation among non-eligible employees grew from 16% to 38%, meaning auto-enrolment has had a tangible positive effect outside of its target beneficiaries. Workers may be ineligible for auto-enrolment through earning under the threshold of £10,000 p/a or being under the age of 22. The increase in non-eligible participation in workplace pensions has been driven by an increase in both the public and private sectors, with participation increasing by 19% and 23% respectively. Whilst non-eligible workers have benefited from the policy, the same cannot be said for self-employed people. For the self-employed, participation in all pensions has remained below 20% since auto-enrolment was implemented.

Of course, as with most policies, the story isn’t completely rosy. There is no requirement to automatically enrol the lowest paid workers onto workplace pensions. Due to their lower levels of disposable income, these individuals are also less likely to invest in a private pension, meaning they are acutely at risk of pension poverty in the future. This factor is especially prevalent in women, who work part-time in higher proportions than men. As discussed above, auto-enrolment also seems to have allowed self-employed people to fall through the gap. Perhaps quite worryingly, auto-enrolment may contradict its aim of improving retirement income. People may assume the minimum saving requirements are adequate to sustain a particular standard of living, and fail to invest more into their pension, or establish a private pension. More needs to be done to educate society about retirement income to address this issue.

Whilst auto-enrolment has been around for 10 years, a couple of reviews have assessed its efficacy and produced suggestions on how to improve it. A 2017 review by an external advisory group recognised the problems associated with the exclusion of younger people, and lower earners, and recommended lowering the enrolment age to 18, as well as removing the lower earnings limit. The government has expressed its commitment to implementing these recommendations, suggesting that these amendments will be made by the “mid-2020s”. Nevertheless, a Private Member’s Bill aiming to implement these recommendations is currently passing through parliament, with a second reading expected in the Commons this parliamentary session.

By David Dike