Summary

As one of our members prepares to embark on the incredible challenge of rowing over 2000 miles, circumnavigating Great Britain, and collecting invaluable marine data in the process, this week’s chart takes a slightly different angle, assessing the value of environmental degradation from plastic use in various sectors.

What does the chart show?

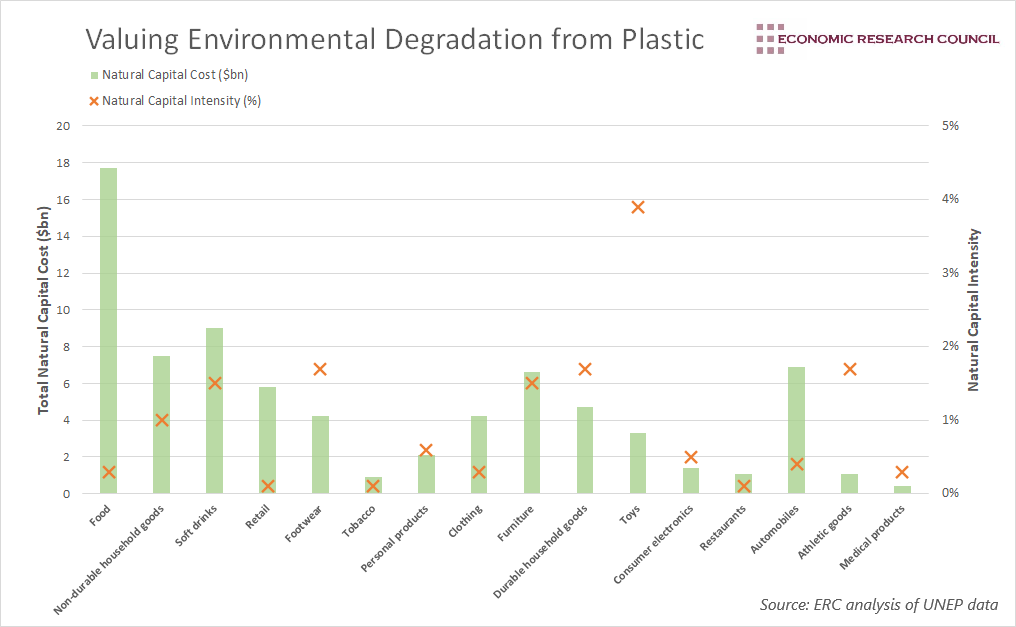

The chart displays the total natural capital cost, as well as the natural capital intensity, of plastic use in various consumer goods. Natural capital includes natural resources such as clean air and water that companies utilise to produce goods and services. Natural capital cost thus uses natural capital valuation techniques to estimate the value of environmental goods and services in the absence of a market price, indicating the value that companies would have to internalise if held fully accountable for the impact of their production. Natural capital intensity is simply the natural capital intensity as a proportion of the revenue of each sector and indicates the proportion of revenue at risk if companies were held fully accountable for the impact of their plastic use.

Why is the chart interesting?

Since the 1950s, the manufacture of plastics has increased drastically, to the point where we now produce around 420 million tonnes each year. Plastics contribute to significant environmental degradation, especially considering that only 9% of manufactured plastic has ever been recycled. Disposal of plastic is not the only issue, however, as over 75% of the impacts associated with plastic occur in the upstream section of the supply chain, between the extraction of raw materials and the manufacturing of plastic feedstock. This week’s chart aims to capture both of these impacts within specific sectors.

Firstly, the chart displays the overwhelming contribution that food’s use of plastic makes to the total natural capital cost. With the increased demand for fresh, packaged food, and ready-made meals, the food sector has relied on plastics to the detriment of other materials. As such, food contributes to over 23% of the estimated $75bn worth of environmental damage associated with the use of plastics. Whilst plastic packaging has reduced waste and extended the shelf life of certain foods, it has significantly impacted pollution. Food wrappers and containers are among the main items collected during coastal clean-ups. Whilst these downstream effects are clear to see, environmental damage arising from upstream activities is larger in magnitude, with almost three-quarters of these impacts occurring upstream. Greenhouse gas emissions and land/water pollutants in upstream production each account for a greater value than the entirety of all downstream environmental degradation. The International Food Policy Research Institute place the blame firmly on the door of single-use plastics. They suggest that 79% of single-use plastics end up in landfills, while 12% are incinerated. In addition to this, they estimate that there is a piece of plastic waste per meter of shoreline across the globe, and 18,000 pieces of floating plastic per square kilometre of ocean.

Whilst food makes the largest contribution to natural capital costs, it has one of the lowest natural capital intensities in plastic. In essence, its revenues are determined to a lesser degree by the natural capital costs it creates. As such, if costs were to be internalised by companies, the financial risk associated with plastic use in this sector is lower than in many other sectors displayed in the chart. Toys fall on the other end of the scale, contributing a relatively small amount to the total natural capital cost of plastic use (4%), but having a natural capital intensity of almost 4%. In essence, for the same amount of revenue, the toy sector produces 13 times the cost of environmental damage from plastics. As such, policy must be targeted at reducing the magnitude of plastic pollution in some industries, and the proportion of plastic used in others. Whilst the overall aims of both are to reduce environmental degradation, the tools needed will be subtly different.

When assessing plastic within packaging alone, the most significant impact is greenhouse gas emissions generated during the processing of raw materials, followed by land and water pollution. The natural capital cost of plastics in the marine system is estimated to be $13bn. It is important to note that within the data used to create this chart, some significant impacts, such as microplastics have been ignored. This is largely due to a gap in research on microplastics within the scientific community. The World Health Organisation recently stated, “further research is needed to obtain a more accurate assessment of exposure to microplastics”.

To help fill this gap in research, one of our members is involved in an incredible initiative, collecting microplastic samples around our coastline by rowing the whole way around Great Britain. In addition to microplastics, they’ll collect data on environmental DNA, underwater noise, salinity, and temperature, working in partnership with the University of Portsmouth, and raising money for London Youth Rowing. More details about the project, as well as information on sponsoring the initiative, can be found below.

Links

Support the University of Portsmouth

By David Dike