Summary

Free school meals (FSM) try to level the playing field and allow children to reach their potential. Despite this, outcomes are consistently lower for children from disadvantaged backgrounds. Tackling intergenerational poverty requires a holistic approach, encompassing factors within and outside of school.

What does the chart show?

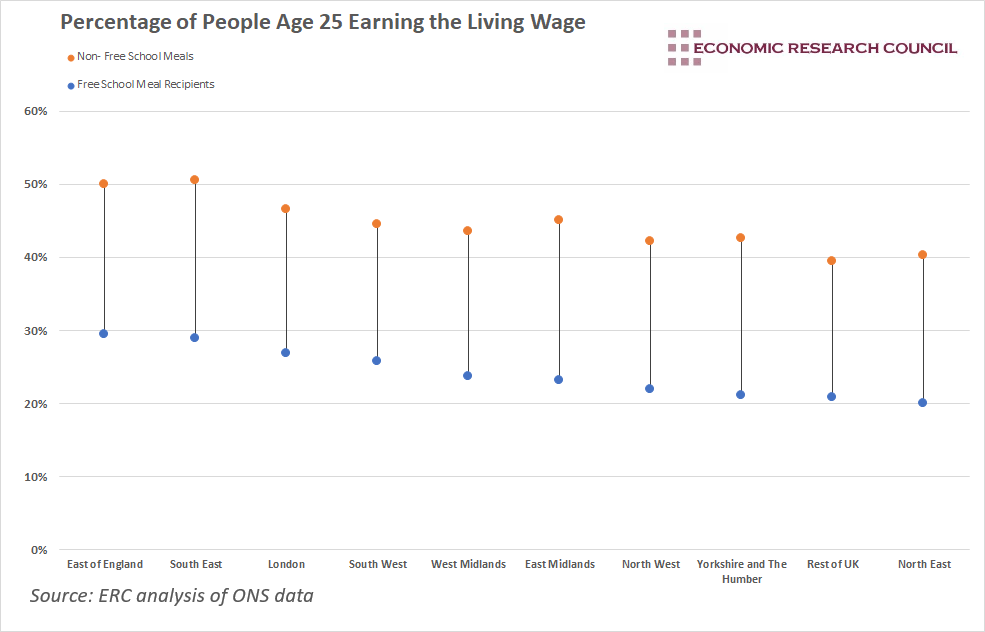

The chart shows the proportion of people at age 25 who earned above the living wage in each region. Blue dots represent people who received free school meals, whilst orange dots represent those who did not. The data starts from the tax year ending 2012 and ends in 2019.

Why is the chart interesting?

Free school meals aim to provide a basic level of sustenance to growing children, ensuring that poverty does not exclude them from gaining the nutrition they need. Providing children with a healthy lunch is supposed to ensure they can participate in a meaningful way in the classroom, mitigating against the risk of hunger impacting their cognitive abilities. In theory, it levels the playing field, assisting disadvantaged children to reach their full potential.

With this in mind, the chart shows some interesting and potentially worrying outcomes. We can see that in every part of the UK, people who received free school meals were significantly less likely to earn above the living wage. On average, the proportion of non-free school meal people earning above the living wage was 20% above those that received free school meals. In fact, earnings are not the only measure showing a difference between the groups. FSM-eligible students are 23% less likely to be in sustained employment compared to peers who were not eligible for FSM, three times more likely to be on out-of-work benefits, whilst just 0.3% of FSM eligible students received top grades in Maths and English GCSE in 2019, compared to 1.5% of non-FSM students.

Does this mean the policy has failed? A number of studies have found that free school meals can increase students’ ability to learn, improve their productivity as well as their mental health, although it is not a silver bullet.

As such, closing the opportunity gap in education, through the provision of free school meals or other policies such as the pupil premium, cannot be done in isolation. The relationship between disadvantage, low educational attainment, and outcomes later in life seems to be part of a broader process, where disadvantage transmits intergenerationally. Research has shown that a number of considerations impact children’s outcomes, such as their experience early in life, the strength of the relationships they form, and the activities they engage with outside of school. These are all determined by a complex web of factors; attention needs to be paid to them in order to meaningfully impact intergenerational disadvantage.

By David Dike