Summary

As the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme draws to an end, we present recent statistics on furloughed staff throughout the pandemic. Younger and older people were both more likely to be furloughed compared to those in between. This presents future challenges for people in both groups. Those with high levels of education have been less likely to be placed on furlough, while the industries that were most and least effected correlate with the extent they have been able to remain open through the pandemic. Use the triangle by the title to toggle between charts.

What does the chart show?

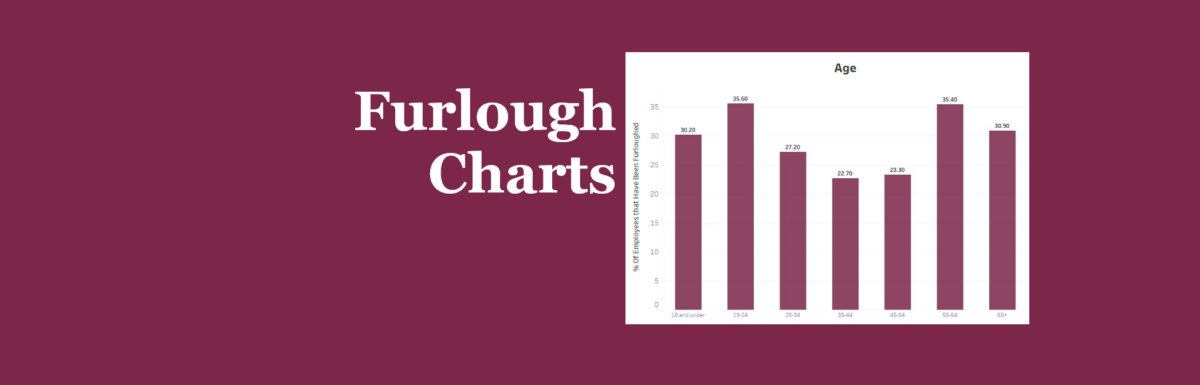

This week’s chart takes a dive into the characteristics of furloughed staff through the course of the pandemic. The ‘Age’, ‘Highest Qualification’, and ‘Industry’ chart all show the number who were furloughed in each subgroup as a percentage of the total number of people in each group.

Why is the chart interesting?

The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme has been praised for limiting adverse effects in the job market, that are likely to have been seen in its absence. Nonetheless, being placed on furlough is an inadequate substitute for gainful employment, especially due to the well-researched effects of economic inactivity. Without actively operating within the job market, swathes of people have risked a decline in their skills, especially if furloughed for a sustained amount of time. The data above goes some way to identify those most at risk of this.

Age shows an interesting trend when assessing the proportion of people furloughed. We can see that both younger (under 25) and older (55+) people faced a greater risk of being furloughed that anybody else. The large proportion of young people is concerning due to the potential labour scarring effects this may have through their career. On the other side of the spectrum, the end of the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme will be particularly worrying for older workers who have not gone back to their role after being on furlough. Research from the Institute of Fiscal Studies has suggested that older workers typically have less experience of searching for work, and are less likely to change occupation. This could be a significant issue if the post-covid economy fails to resemble the past.

Intuitively, holding higher qualifications has been associated with a lower prevalence of being placed on furlough. Degree holders we less than half as likely to be furloughed compared to those who had A levels as their highest qualification, and even less so compared to those who held a GCSEs as their highest. This likely reflects additional job responsibilities for those with higher qualifications, making it less likely for them to be placed on furlough.

The proportion of workers furloughed by industry again follows conventional wisdom, with industries that were hit by lockdowns morel likely to place staff on furlough. Business in the accommodation and food industry placed nearly 7 out of 10 staff on furlough, as restaurants closed and foreign travel was heavily restricted. As the UK opens up and some semblance of normality returns, workers within this sector should largely return to active employment. The picture is less clear within other industries. Almost 4 in 10 staff within the wholesale and retail trade have been placed on furlough. The closure of stores on the high street has largely been met an expansion of online provision. We have discussed the extent to which this will remain on previous Charts of the Week. If the accelerated shift towards online retail does persist, concerted efforts to retrain will likely need to be made by retail staff that had been furloughed.

We also see that workers in industries providing essential services have been significantly less likely to be placed on furlough. Public services, health, agricultural, and educational staff were all placed on the government’s list of essential workers, and had the lowest probability of being furloughed.

The issues raised above must be paid attention to as time goes by. The potential for sections of the population to face long term unemployment and be significantly deskilled is quite clear should we face a lack of labour mobility. As the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme has only just ended, we must watch the trajectory of unemployment, keenly analyse those falling into it, and be ready for a focussed policy response should it be required.

By David Dike