Summary

Financial markets have been in crisis mode ever since the budget. Institutions called on the bank of England to step in, which they did, but were we ever any close to a catastrophe? This week’s chart analyses the impact that instability in the bond market had on defined-benefit pension funds.

What does the chart show?

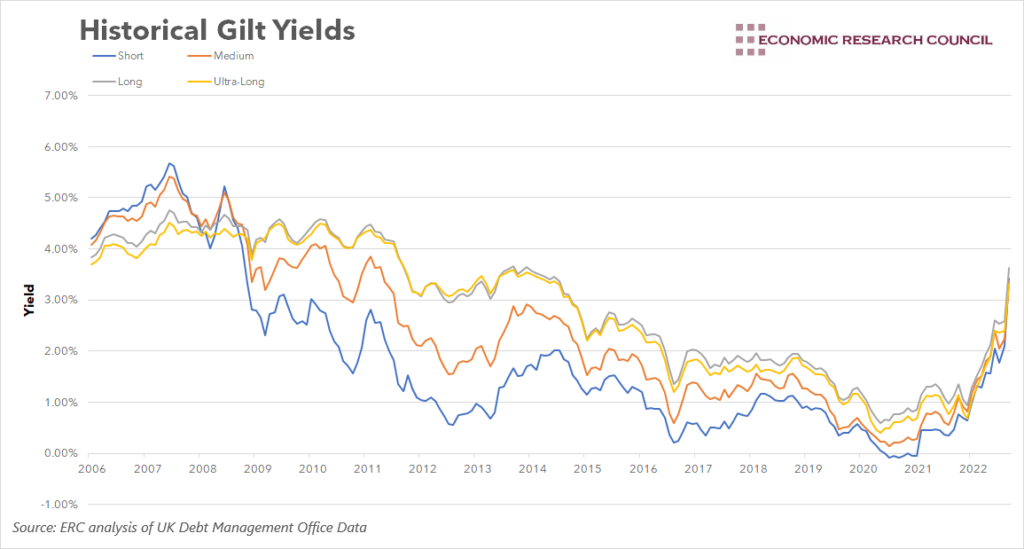

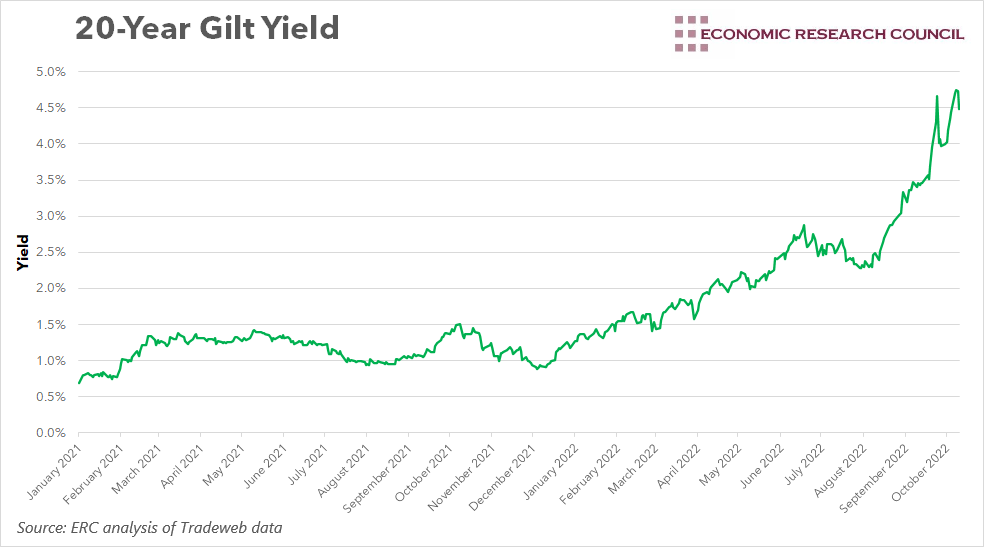

The chart above displays historical monthly yields for short, medium, long and ultra-long-dated gilts between January 2006 and September 2022. In addition to this, the chart below hones in on recent weeks, to show the daily yield for 20-year gilts.

Why is the chart interesting?

Since the onset of the financial crisis, the yield on gilts has been on a downward trajectory. These constitute 50% of all assets held by private-sector pension schemes. As yields fall, these gilts pay out less to pension funds, leaving defined benefit schemes with less to pay out to pensioners. Two reasons for falling yields over this period are the historically low Bank Rates and large amounts of quantitative easing that the Bank of England has engaged in, as a direct result of the financial crisis. Lower Bank Rates made gilts more appealing due to their comparably better return, thus increasing their price and lowering their yield. Quantitative easing artificially increased demand for gilts, increased their price and lowered their yield. Ultimately, falling bond yields mean defined-benefit pension funds’ discounted liabilities rise by more than the value of their assets, making it more difficult to service these liabilities.

After an extended period of falling yields, the story changed at the start of 2021. The chart shows that the yields on each type of bond increased drastically from this point. Increasing levels of growth and inflation associated with the Covid recovery drove gilt yields higher through 2021. Generally, it was expected that interest rates would need to rise over time, which contributed to the rise in yields. As I’m sure you’ll be aware, interest rate expectations have continued to increase through 2022. In addition to that, the infamous mini-budget brought about serious questions regarding the government’s fiscal prudence. The roughly £45bn of unfunded tax cuts, most of which have now been reversed, made UK debt less appealing and decimated demand for gilts. The chart portrays this with a sharp increase in bond yields in recent weeks.

The general narrative has been that this increase in bond yields and the subsequent impact on defined benefit pension funds had been a disaster. After all, many of these pension funds contacted the Bank of England, urging them to purchase gilts. However, in the aftermath of the financial crisis when yields were falling, defined-benefit pension funds’ ability to meet their liabilities also fell. How can falling yields and rising yields both be negative for these funds? Well, rising yields are beneficial for pension funds in the long run. It allows the cost of providing a guaranteed income to fall and improves the position of defined-benefit pension funds. The crucial factor to the events of the last few weeks involves Liability Driven Investments. Defined-benefit pension funds need to ensure their assets generate enough cash to meet their liabilities. LDIs use derivatives to match assets to liabilities to ensure defined-benefit pension funds do not risk a shortfall in funds to pay pensioners. Pension funds post collateral against these LDIs, and the amount of cash needed rises or falls depending on the value of the underlying assets tracked by these derivatives. Up until recently, rates had been rising in a stable enough manner, allowing yields to rise similarly. As such, pension funds had enough time to find collateral to post against these LDIs. When yields dramatically increased (and gilt prices fell), these funds had less time to find the collateral, meaning many began to sell their most liquid assets, gilts, to cover their LDI derivatives. Widespread selling of gilts exacerbated the problem, putting further downward pressure on gilt prices.

Enter the Bank of England. Despite committing to quantitative tightening just weeks before, they agreed to ease the instability in the bond market by buying gilts worth up to £65bn, essentially easing the downward pressure on price by artificially creating demand. Rather than stepping in to save these pension funds, this intervention was mainly about liquidity. Pension funds were simply struggling to find the cash to use as collateral, and as mentioned earlier, the high bond yields placed them in a better financial position in the long term. Rather than seeing the intervention as something that was supposed to save pension funds, it should be seen as an act to stabilise bond markets, where the effect of a bond market collapse would have had serious implications for financial stability.

By David Dike